The third Reconsidering Russia podcast, featuring Dr. Yuri Zhukov of the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor about the recent conflict in Ukraine’s Donbas. Dr. Zhukov is an Assistant Professor of Political Science and a Faculty Associate with the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research.

Tag Archives: donbas

Equalization and Dehumanization in Eastern Ukraine

Dehumanization is a central component of war propaganda. By removing the humanity of individuals and reclassifying them as anonymous “others,” it becomes easier for combatants in a war to kill them. Such is the case with eastern Ukraine, a conflict rife with dehumanization.

In the Ukraine conflict, the greatest victims of such dehumanization are the 5.2 million Russian-speaking civilians of the industrial eastern Ukrainian region of the Donbas. Lifelong residents, they are caught in the crossfire between the pro-Russian rebels and the pro-Kiev militias. Regardless of their political sentiments, the locals have been cast by officials in the Kiev government variously as “terrorists,” “Colorado beetles,” “Moskali,” and “subhumans.” Very little distinction is made among the civilians, the actual rebels, and the rebels’ supporters in Moscow. Civilians who remain in rebel-held territory are often considered “traitors” by the mere fact that they chose to remain in their homes.

This lack of clarity, combined with attacks against east Ukrainian civilians by far-right battalions (accused of war crimes by Amnesty International), has driven the majority of the population to support the rebels. If they were ambivalent toward the rebel cause before, the rhetoric and actions of the Kiev government and its supporters changed their stance. Further, since the start of the conflict, the dehumanization has extended to anyone in Ukraine deserting the army, dodging the draft, or explicitly voicing opposition to the war, like the journalist Ruslan Kotsaba. He was arrested by Ukrainian authorities for openly expressing his views in a YouTube video and now potentially faces 15 years in jail for treason. Amnesty International has declared him a prisoner of conscience.

The dehumanization of eastern Ukrainians has also spilled into the discourse of Western politicians, pundits, and analysts. One of the most vocal of these, the Ukrainian-American academic, Alexander Motyl, has called the people of the Donbas “the most retrograde part of [Ukraine’s] population” and has attempted on more than one occasion to draw parallels between them and white US southerners who supported Jim Crow. His discourse has only fueled the flames of the conflict, pitting Ukrainians against Ukrainians. It also drew strong criticism from Lev Golinkin, a writer originally from Kharkiv, in The Huffington Post.

Motyl was not alone. Other Western commentators have also dehumanized the people of eastern Ukraine. Further, this dehumanization has seeped into a general dehumanization of all things Russian. From the start of the crisis in Ukraine, the Ukraine-EU Association Agreement was presented to Western readers as a “civilization choice” for Ukrainians between a “civilized Europe” and a “barbaric, Asiatic Russia.” During the Euromaidan protests in December 2013, Sweden’s former Foreign Minister Carl Bildt, the co-architect of the EU’s Eastern Partnership (EaP) program, tweeted that the growing conflict between the protestors and police symbolized “Eurasia versus Europe in [the] streets of Kiev.” Even more extreme, former Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili declared Moscow to be the “new Tatar-Mongol yoke.”

Such characterizations and stereotypes imply a superiority of one people, culture or civilization over another. They allude to destructive racial ideologies from the darker chapters of the 20th century. The implicit message is exclusion and separation, not cooperation and engagement. These discursive Social Darwinist formations have absolutely no place in the discourse of the 21st century. Yet, somehow they persist.

There is also dehumanization in the Russian media. However, it is important to highlight the distinct nuances here. Dehumanizing rhetoric in the Russian media has largely concentrated around liberal oppositionists who are derided as “fifth columnists” and potential “traitors.” The discourse is purely internal, though it is undoubtedly exacerbated by external affairs. Western policies toward Russia and the former Soviet space since the dissolution of the USSR have fueled greater distrust and suspicion on the part of the Russian government toward the opposition, making freedom of speech more difficult. In this respect, one can make a very strong case that Western policies like NATO expansion, missile defense, the unilateral cancellation of the IBM treaty, or the sponsorship of pro-Western revolutions in ex-Soviet states have harmed the development of democracy in Russia, not helped it.

This stands in contrast to the dehumanization of east Ukrainian civilians and Russia by the present Ukrainian government and its supporters in the West. In fact, official Russian-backed media has refrained from engaging in any dehumanizing rhetoric toward the people of Ukraine proper. True, they have liberally used terms like “Nazis,” “fascists,” and “Banderists.” However, they have not used these terms to describe the Ukrainian people as a whole. Rather, they have used them to describe the government in Kiev, a very important distinction. In Moscow’s view, there is a clear delineation between what is regarded as “the government” and “the people.”

Indeed, in the Russian worldview and discourse, the Ukrainian people are seen as either a deeply kindred people or an extension of a greater East Slavic whole, along with Russia and Belarus. Further, a larger partition of Ukraine, which would certainly involve more conflict, is decidedly not in Russia’s interests. Therefore, Moscow has little to gain from dehumanizing a large number of Ukrainian civilians through the mass media. This explains why they have been careful to distinguish between the government of Ukraine and the people. In fact, in the Russian narrative, the people of Ukraine are often presented as being “naive” or “duped” by Western policies, though their struggle against corruption is viewed understandably.

By contrast, the distinction between the breakaway governments of Donetsk and Luhansk and the locals living there is barely made by the Ukrainian government. This is why the dehumanization of civilians in the Ukrainian media and in the Russian media simply cannot be compared or “equalized.” Equalization often has the intended goal to bring people together. By creating a false symmetry, the thought is that people will recognize the flaws of “both sides” and work toward peace. The goal is indeed noble, but the aims of achieving it, which obscure the facts of a given situation, are questionable.

Analytical equalization has likewise been applied to another part of the Soviet Union: the conflict over Nagorny Karabakh between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Armenia is a hybrid regime among the ex-Soviet states, embracing elements of liberalism and authoritarianism. Yet, it largely has a free press and free media (including a Daily Show-style satirical news program). Armenia simply cannot be described as an “authoritarian state.”

This is in contrast to Azerbaijan, which is indeed an authoritarian state. The country boasts a pervasive personality cult of the ruling Aliyev family, especially the current president Ilham and his father, Heydar. Dissent is systematically muzzled and there is little room for free expression or free speech.

An objective assessment would illustrate the differences that exist between the two states. Yet, Western commentators, eager for an immediate peace over Karabakh, gloss over these differences and instead generalize that “both are exactly the same.” Such a formation excludes critical thinking and prevents one from observing nuances between the conflicting parties. Consequently, the search for that all-elusive resolution becomes even more challenging.

Overall, the key to ending any war or conflict is to first and foremost stop the senseless dehumanizing and malicious rhetoric. Dialogue becomes possible when people begin to realize their common humanity – that which they share. Consequently, instead of talking in exclusionary terms of “Europe” vs. “Eurasia,” “West” vs. “East,” we should be reflecting collectively in terms of cooperation among all peoples on the vast Eurasian landmass, from Lisbon to Vladivostok. Only then can there be true peace.

Correction (8 March 2015): It has been called to my attention that I made a typo on this piece. I accidentally referred to Amnesty International declaring Ruslan Kotsaba as a “prisoner of consciousness” as opposed to a “prisoner of conscience.” This has now been fixed, but the mistake was somewhat ironic, given concerns of Europe “sleepwalking into war.” Kotsaba was indeed “conscious” enough to see that danger.

Do the Donbas Rebels Want to Establish an Overland Corridor to Crimea?

Numerous observers of the recent events in Ukraine and Mariupol have concluded that the Donbas rebels seek to establish an overland corridor (or “land bridge”) to Crimea on behalf of the Kremlin. The claim, often repeated by pundits in the West, was also echoed by at least one Russian political analyst (Sergey Markov).

However, is this really the case? Do the Donbas rebels really want to establish an overland corridor to Crimea?

The facts and realities of the situation indicate, simply, “no.”

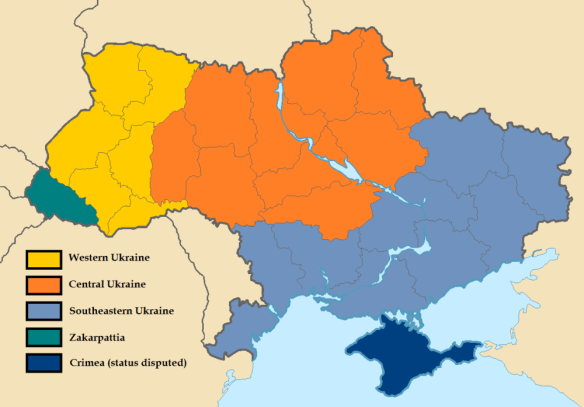

First and foremost, the Donbas region as a whole (including both Kiev-held and rebel-held areas) has no geographic link whatsoever with the Crimean peninsula (see the above map). In order to establish a land bridge to Crimea, the rebels would need to invade the neighboring oblasti of Zaporozhia and Kherson on the Black Sea, both of which are not considered part of the Donbas.

Such an action would create a serious escalation of the Ukrainian conflict, something that Moscow has continuously stressed it wants to avoid. There is also the question regarding the rationale for the creation an overland corridor to Crimea when Russia has already invested a lot to build a bridge to the peninsula across the Kerch strait to the Krasnodar Krai.

Even more importantly, since August, the rebels, especially the leader of the Donetsk Republic, Aleksandr Zakharchenko, have made it clear on numerous occasions that they do not have any territorial ambitions outside of the Donbas region.

In fact, in light of the most recent fighting between Kiev and the Donbas rebels, Zakharchenko vowed to push the front to the borders of the Donetsk oblast so that “no shells can fall on Donetsk.” The recent Mariupol hostilities need to be comprehended in this context.

Mariupol is important to the rebels, not as a potential part of an overland corridor to Crimea, but as part of the Donbas region and part of the Donetsk oblast more specifically. In fact, it is the second largest city in the Donetsk oblast after Donetsk. It is also a major port, giving the rebels another “life line” to Russia. These are the reasons for its importance.

Ukraine’s Rebel Elections

The results of the election in the rebel-held areas of Ukraine’s Donbas were not a huge surprise. Igor Plotnitsky, the President of the self-proclaimed Luhansk Republic, won by 63% of the vote while Aleksandr Zakharchenko, the President of the self-proclaimed Donetsk Republic, won by 75% of the vote.

In both cases, it is worth noting the high voter turnout which exceeded 60% in both regions, in contrast to the low voter turnout (in the 30% range) across the border in the portions of the Donbas still held by Kiev. Therefore, the regional electorate illustrates a preference for the rebel leadership.

Notably, when the first steps were taken toward declaring republics in Donetsk and Luhansk in April, much of the population, though pro-Russian, was indifferent to the rebel cause. What changed popular opinion was the violent “anti-terrorist operation” launched by Kiev and the start of the Donbas war, in which thousands of people perished and over a million became refugees. The conflict included numerous human rights violations and war crimes. These were committed by both sides, but especially by Kiev and the notorious far-right volunteer battalions serving under its watch, such as the feared Azov Battalion. Civilian areas were shelled constantly by Kiev’s forces and, according to Human Rights Watch, Kiev also used cluster munitions. Buildings and infrastructure lay in ruins as do people’s livelihoods. The people of the Donbas are angry, and popular support has now been galvanized in favor of the rebels.

Something else changed too. Though the proclamation of the rebel republics was primarily driven by locals, its leadership was largely under the influence of Russian nationalists from across the border in Russia. However, over time, the leadership of the rebel regions has become increasingly more local, as clearly seen in the cases of both Zakharchenko and Plotnitsky. The revolt itself has also become more local and more Donbas-centric. The rebels have even adopted a “national anthem” called “Вставай, Донбасс!” or “Arise, Donbass!”

Zakharchenko, a former coal mine electrician from Donetsk, has an especially “local” character about him which may partially explain why he won by such a large margin. At a press conference on 24 August, he and his defense minister Vladimir Kononov (another Donbas native) disavowed any association between the rebels and the historic “Makhnovtsy.” This was a reference to a history that the Donbas locals would known best, that of the anarchist Nestor Makhno whose “Free Territory” during the Ukrainian Civil War of 1917-21 included portions of the present-day Donetsk oblast. Zakharchenko also seemed to distinguish the Donbas as a region from the rest of Ukraine including even the rest of the Southeast, making statements such as “We didn’t come to you in Kiev, Dnepropetrovsk, or Zaporozhia. Leave us [the Donbas] alone. Let us live free and in peace.” He likewise emphasized the hard-working and working-class character of the Donbas people, an amalgam of Russian-speaking Ukrainians, ethnic Russians, and mixed Russo-Ukrainians.

It also worth noting the specific time in which both Zakharchenko and Plotnitsky assumed office. This was in early August, around the same time that Moscow decided to definitively give the rebels military aid to turn the tide against Kiev. Putin was under pressure from the hardliners in the Kremlin to help the rebels for some time. When he finally decided to do so in August, it is likely that one of the conditions for Moscow’s support was that the leadership of the rebel movement had to become more “local.” This would explain the rise of more local figures, such as Zakharchenko and Plotnitsky, to leadership positions in early August.

Overall, it is clear that the only realistic solution for the protracted conflict in the region can be peace. The rebels are ready for talks with Kiev. However, with the strengthened position of “war parties” in Ukraine’s Rada, such a prospect may be diminished or even lost, drowned out by calls from nationalists in Kiev to continue the war. If this does happen, the Donbas rebels are unlikely to back down.

Independence Day

Today, on 24 August, Ukraine will celebrate its independence from the Soviet Union. Yet, if one observes the developments in Ukraine for the past two decades, it quickly becomes apparent that there is very little to celebrate. In the 23 years since the breakup of the USSR, more than seven million people have emigrated from the country. Now, as the conflict in the Donbas continues, that figure is over eight million and, with Russia’s incorporation of Crimea, this number becomes nine million. Between the 2004 Orange Revolution and the recent Maidan Revolution alone, approximately four million people have departed from Ukraine.

Additionally, the Ukrainian economy is in decline and default and, today, it stands on the precipice of total collapse. Even IMF-sponsored “reforms” will not be enough to bail out Ukraine’s mammoth debt and the added “bonus” of IMF-backed austerity will send the population reeling. Likewise, corruption has not halted at all in Ukraine, and has only become worse. Even the Maidan Revolution was not able to fundamentally change this problem in Ukrainian society. Today the Ukrainian political elite remains just as corrupt as it was when the Maidan Revolution broke out in November 2013. In the Rada, fist fights between rival politicians continue and it is unclear whether or not Maidan has also eased the country’s problems with poverty, unemployment, human trafficking, or organized crime.

Since the 2004 Orange Revolution, the divisions in Ukrainian society have become worse. The Ukrainian nationalists of Galicia today hate Russia or anything Russian-oriented with greater intensity than ever. By contrast, those Russian-speaking Ukrainians in South and Eastern Ukraine continue to reject any notion of membership in NATO or the EU, and they refuse to sever any ties with Russia. Meanwhile, divisions persist among Central Ukrainians while the Rusyns of Zakarpattia view the situation with exasperation.

In the Donbas, war between official Kiev and pro-Russian rebels has given way to a humanitarian catastrophe. Throughout the conflict, Kiev’s forces, including rogue far-right militias like the feared Azov battalion, have relentlessly shelled and attacked civilian infrastructure and the area’s Russian-speaking civilians. Refugees have fled en masse to Russia while others have escaped into more peaceful regions of Ukraine. Thousands died in the conflict, not only civilians, but also Ukrainians from other parts of Ukraine who were recruited to fight against their own ethnic kin. Families have become ideologically split over the conflict, while the industry in the Donbas, which is so crucial to Ukraine’s economy, has come to a total standstill. Cities like Slavyansk are in ruins. Everyday livelihoods of neighborhood bakers, doctors, and others have been disrupted. Daily institutions like grocery stores, pharmacies, banks, and schools have been destroyed or closed. Questions still remain unanswered with regard to the tragic shootdown of the MH17 Malaysian airliner.

Now, as Ukraine prepares to celebrate its 23rd independence day, reports are rife that the government of President Petro Poroshenko will seek to capture the city of Luhansk at any cost. This inevitably means more attacks on civilians, more indiscriminate shelling, and more destruction. Instead of working to declare an “independence day peace,” he is instead alienating more of his citizens against him. As a catastrophe consumes the Donbas and problems persist throughout the rest of Ukraine, including an impending economic collapse, ordinary Ukrainians will inevitably ask: “What is there to celebrate?”

Ukraine: Where Nation-Building and Empire Meet

As the Ukraine crisis continues, there are debates emerging with regard to the relationship between Russians and Ukrainians, in language, culture, and history.

The vast majority of ordinary Russians view Ukrainians, though linguistically distinct, as being a fraternal East Slavic nation, closely bound to Russia by culture, history, and intermarriage. They further assert that Ukraine is an integral part of Russian civilization, owing to the particularly special significance of Kiev to both Russians and Ukrainians. More nationalistic Russians go even further and claim that Ukraine is merely a “concept” and that the people known as “Ukrainians” are merely an extension of the Russian nation who speak a dialect of Russian.

Some Ukrainians, particularly in the Central part of the country, would sympathize with the argument that Russians and Ukrainians are a fraternal people. In the Russian-speaking Southeast this would be further elevated to Russians and Ukrainians being “the same people.” However, as one might imagine, the nationalist discourse in Western Ukraine, particularly Galicia, is radically different. To Ukrainian nationalists, Ukrainians are “completely different” from the Russians. They have they own culture, language and history which they believe is “entirely disconnected” from anything to do with the Russians. Some more extreme Ukrainian nationalists even claim that the Ukrainian language is not only distinct from Russian, but also distinct among all Slavic or even Indo-European languages as well.

Of course, the truth exists somewhere in-between these conflicting narratives. It is true that Ukrainians do speak their own language and that there are aspects of Ukrainian culture that are indeed unique to Ukrainians. However, it is also true that Kiev is the common point of origin for all East Slavs including Ukrainians and Russians; that at one time in their common history, they used to speak the same language (Old East Slavic); and that the contemporary Ukrainian and Russian languages (though not exactly the same) are indeed very similar. It is also true that the Ukrainians and Russians have much in common in terms of culture, and they have both had a major impact on one another. Examples of this cultural exchange include the squat-and-kick prisyadka dance move and the beet soup borscht, both of Ukrainian origin but deeply influential in Russian culture. Nikolai Gogol was a famous Russian-language author of Ukrainian origin who often included Ukrainian themes in his writings, e.g., Taras Bulba. The great Russian painter Ilya Repin, though himself an ethnic Russian, was born in Ukraine and also included many Ukrainian themes in his work, signaling his great love for his fellow East Slav brothers.

Intermarriage is also a major component of the Russo-Ukrainian relationship. Nikita Khrushchev and Mikhail Gorbachev were both products of mixed Russo-Ukrainian parentage; their wives, Nina Kukharchuk and Raisa Titarenko, were both fully Ukrainian. Another former leader, Lenoid Brezhnev, was also of mixed Russian-Ukrainian heritage while another, Konstantin Chernenko, came from a Russified Ukrainian family. In music, the famous Russian rock star Yuri Shevchuck is Ukrainian and the Bessarabian-born Russian tango singer of the 1930s Pyotr Leschenko was also of Ukrainian background. Additionally, the dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, and the great Soviet rocket engineer Sergei Korolyov were all born to mixed Russian-Ukrainian parents.

Kievan ruler Vladimir the Great was baptized at Khersones (in modern-day Sevastopol) and converted the Kievan Rus’ to Christianity in the 10th century. Vladimir is widely revered by all East Slavs (including Russians and Ukrainians) to this day.

Rus’, Malorussia, Ukraine, and the Politics of Identity

Another aspect of the very close relationship between the Russians and the Ukrainians is the historical development of the identity of the Ukrainian people. At one point, all of the East Slavs (Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Carpatho-Rusyns) used to comprise a single people – the people of the Rus’ – who used to speak a single language known as Old East Slavic. Their faith was Orthodox Christianity. The only exception to this were the Kievan territories of Galicia and Volhynia. Forming the westernmost regions of the old Rus’, Catholic and Polish influence was very strong in these areas, particularly Galicia, and their princely families even intermarried with nearby Catholic Polish and Hungarian houses. Significantly, while there was a distrust of Catholicism in the other Rus’ territories further east, in Galicia and Volhynia, Catholic and Western ideas were welcomed and fully embraced. This early cultural division would later play a role in Ukraine’s regional identity differences centuries later.

Another key factor was language. In the 13th century, the Kievan Rus’ fell into decline and became subjected to the Mongol invasions. Its western principalities (largely correspondent to much of modern-day Central Ukraine and Belarus) were absorbed by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which later unified with the Kingdom of Poland at the Union of Lublin in 1569, forming the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The gradual “break-up” of the single Old East Slavic language into several different languages – Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Carpatho-Rusyn – occurred during this period. Yet, even into the early 20th century, many of these East Slavs still self-identified as “Rusyni” and spoke a language which they called “Rusynski,” both referring to the old Rus’ state.

Foreign rule further created a new dimension to the situation which involved religion. Rus’ lands under Mongol rule remained free to worship and practice their Orthodox Christian faith. By comparison, in those Rus’ lands under Polish-Lithuanian rule, Orthodoxy was at first tolerated. Later, however, the separateness in faith concerned the Polish monarchs as the Orthodox locals of the historic Rus’ lands saw their affinity not with Catholic Poland or Western Europe but with the world of Russian Orthodoxy. As such, Orthodox Christians were persecuted under Polish rule until in 1595, in exchange for an end to this persecution, the Orthodox clergy of the Polish-ruled lands agreed to the Union of Brest, forming the Ukrainian Greek Catholic (or Uniate) Church. However, in subsequent centuries, as the Russian Tsars later reclaimed the old western Rus’ lands from Poland-Lithuania in the 18th century Partitions of Poland, the Orthodox faith was reintroduced. Significantly, in the Partitions, the Habsburg monarchy in Austria acquired the Catholic- and Western-leaning region of Galicia.

Additionally, an entirely separate situation existed further west in the region of Carpathian Rus’ (Zakarpattia). This distant western region was a borderland frontier area at the time of Kievan Rus’. It fluctuated between the control of Orthodox East Slav Kievan rulers to the north and east and Magyar (Hungarian) Catholic rulers to the south and west. With the fall of Kievan Rus’, this Carpathian territory fell under the complete control of the Hungarian monarchs. Overtime, the close proximity of the Catholic Slovak and Magyar populations combined with the area’s separateness from the other historic Rus’ lands due to the Carpathian Mountains led it to develop its own entirely distinct identity and language (Carpatho-Rusyn). This difference was reinforced with the Union of Uzhgorod in 1646 in which the Orthodox Rusyns joined the Catholic Church as part of the Byzantine rite, forming the separate Byzantine Ruthenian Catholic Church.

As mentioned earlier, the Russian Tsars later reclaimed much of the old western Kievan Rus’ territories in modern-day Ukraine in Belarus during the Partitions of Poland in the 18th century. Orthodoxy was also reintroduced in these regions. The “Rusyni” identity of old persisted among the locals and, during the 19th century, two rival nation-building projects on the territory of contemporary Ukraine sought to supplant this old “Rusyni” identity with a new identity. One was the Malorussian (“Little Russian”) identity, with the name “Little Russia” derivative from old Byzantine maps referring to modern Ukraine as “Lesser Rus'” or “Rus’ Minor.” The Malorussian project claimed that modern Ukraine was a natural extension of the Russian nation. In the Malorussian view, the Ukrainian language that developed from the break-up of Old East Slavic had to be supplanted by a common standard language. In their view, this was to be Russian, a language seen by Malorussian activists as the “successor” of Old East Slavic. Nikolai Gogol, an ethnic Ukrainian who wrote in Russian, was among those who favored Malorussianism.

Opposing Malorussianism, was Ukrainianism. Ukrainianism postulated that the East Slavic language that developed in Ukraine signified the development of an entirely separate ethnic identity, independent of other East Slavs. They called their nation “Ukraine,” a name that like “Malorussia” developed from cartographic toponyms and has been literally translated as “borderland.” Ukrainianists emphasized the unique and distinct culture of the people of the area above all else, with a special emphasis on language and culture. Of course, this did not exclude those who viewed themselves as “Ukrainian” but also saw Russia as a fraternal East Slavic nation nonetheless. The writer Taras Shevchenko is perhaps best representative of the “Ukrainianist” group, writing almost exclusively in the Ukrainian language, though occasionally writing in Russian as well.

Of these movements, Malorussianism was favored by the Tsars who regarded themselves as the legitimate successors to the rulers of the old Kievan Rus’. Consequently, the Malorussianist policies of official Petersburg should be viewed not within the context of an empire attempting to force an assimilation on a “conquered” people, but rather as part of a nation-building project or as part of the great “reunification of Old Rus'” and “gathering of the Russian lands” as the Tsars saw it.

A similar national project was also taking place in Italy, which had just been unified under the leadership of Giuseppe Garibaldi. There, the Italian language, based on Tuscan and the Central Italian dialects, was to become the literary standard. However, in the southern island of Sicily, the locals spoke their own Romance language Sicilian, related to Italian but also distinct in its own right. In Rome, the king regarded Sicilian just as the Tsar regarded Ukrainian, as a backward provincial dialect which, with the expansion of education and literacy, would be eventually supplanted by “clean Italian” or in the Tsar’s case, “clean Russian.” Indeed, like Ukrainian, Sicilian developed distinct from other languages in Italy by virtue of its geographic separation from the mainland and historical invasions of the island by Greeks, Arabs, Normans, Germans, Spanish, and others. Yet Sicily was viewed by Italianist advocates as an integral and historical part of Italy, just as Ukraine was regarded as an integral and historical part of Russia by the educated class, the bourgeoisie, and the aristocracy.

An additional development to all of this was the emergence of three new historical territories overtime. They included Zaporozhia which established itself in the “wild fields” south of Polish-ruled territory in the 15th and 16th centuries. In this region, rebellious Orthodox Christian Cossacks fought against the Polish monarchs. Then, in the 17th century, the area of Slobozhanshchina (or Sloboda Ukraine) emerged around the cities of Kharkiv and Sumy. Finally, in the 18th and 19th centuries, the area of Novorossiya was formed along the Black Sea after the Russian Tsars had finally succeeded in taking Ottoman-held territory along the coast. In all of these regions, Ukrainian (or Malorussian) populations played primary roles in their historical formation and settlement. Further, in all three of these regions, Orthodoxy was the primary faith.

The Malorussian-Ukrainian debate also took place across the border in the Austro-Hungarian-ruled East Slavic territories of Galicia, North Bukovina (Chernivsti), and Carpathian Rus’. There, the debate existed between Ukrainianists and Russophiles (effectively Malorussian activists under a different name). It became even more complex in Carpathian Rus’ ruled under the the Hungarian realm of the dual monarchy, between Ukrainianists, Russophiles, and Rusynists (those who chose to self-identify as Rusyn or Carpatho-Rusyn). In Galicia, where Catholic influence of both the direct Roman Catholic and Uniate strands remained strong, the debate was eventually won by the Ukrainianists. However, in Carpathian Rus’, the debate over ethnic identity still persists to this day. Notably, during this period, many people from these Austro-Hungarian-controlled territories (particularly Galicia and Carpathian Rus’) also emigrated further west in search of opportunity. They arrived in the United States and Canada, establishing the core of what would become the contemporary Ukrainian and Carpatho-Rusyn diasporas of today.

National Identity in the Soviet Era

Original avant-garde poster for Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930). The film is perhaps Dovzhenko’s best-known work and it is part three of the director’s “Ukrainian trilogy” which also included Zvenigora (1928) and Arsenal (1929).

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, the civil war in Ukraine of 1917-21, and the establishment of the USSR, Ukrainianism as a movement won out over Malorussianism. In the 1920s, the new Soviet government undertook a “Ukrainization” policy in the newly-declared Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, as part of its broader nativization or korenizatsiya (коренизация) policy toward nationalities, by promoting and advancing the Ukrainian literary language. This had the effect of encouraging a major cultural and literary renaissance in Ukraine during the NEP that many Ukrainians still fondly remember today. The advent of new art forms, like film, helped advance this renaissance, in which the great Ukrainian filmmaker Aleksandr Dovzhenko played a leading role. A pioneer of early Soviet film, Dovzhenko is credited for not only his contributions to the development of Ukrainian cinema but also for Soviet and Russian cinema overall.

The Ukrainization policies were abruptly halted in the 1930s under Stalin whose NKVD purged the republic of real or perceived nationalists, “kulaki,” and “enemies of the people.” Yet, it should be noted that Stalin was not interested in the Malorussian-Ukrainian identity debate, but more concerned with strengthening his position throughout the entire USSR, and to this end he purged writers and intellectuals in all Soviet republics.

Compounding all of this was the terrible Soviet famine of the early 1930s. The famine hit Ukraine very hard and some Ukrainian nationalist historians even go so far as to assert that what happened was a deliberate attempt at genocide against the Ukrainian people by the Soviet government. However, this fails to take into account the fact that the famine also affected many non-Ukrainians too, including Germans, Poles, Jews, and Russians. Likewise, the famine also hit southern Russia and northern Kazakhstan, two other major cereal-producing regions of the Soviet Union, very hard. Among those who witnessed the starvation was a young Mikhail Gorbachev, a native of southern Russia, who personally experienced the horrors of the terrible famine first-hand. It affected his own family and killed off half of his village.

Millions starved to death in this cruel campaign of forced collectivization and suppression of the so-called “kulaki.” Yet, Western correspondents like Walter Duranty disguised the facts while Stalin and Soviet officials claimed that the campaign had made the “eternally happy” people of the Soviet agricultural heartland “dizzy with success.” Overall, ethnicity meant little to Stalin. Nobody was safe from the terror of the vozhd. He was an equal-opportunity mass murderer.

The Soviet era also saw the rise of industrialization. The heavily industrial coal-mining region of the Donbas (Donets Basin), centered on the cities of Donetsk (also known as Yuzovka or Stalino) and Luhansk (also known as Voroshilovgrad) really emerged during this period. Prior to this, the Donbas had been an area with a mixed Ukrainian and Russian Cossack population divided between historical Sloboda Ukraine, Novorossiya, and the Don Cossack Host. The Soviet era firmly established the Donbas as a unique region in its own right, a truly working-class “Soviet” region where Russian was the primary language. It was in this area that, during the Stalin era, Aleksei Stakhanov and the Stakhanovite movement emerged.

World War II left an indelible mark on Ukraine. In the war, most Ukrainians fought alongside the Russians against the onslaught of the Nazi German war machine. Many Ukrainian villagers in present-day Central and Southeastern Ukraine experienced violent atrocities at the hands of the hated Nazi invader and the country’s sizeable and historically significant Jewish community was decimated by the Holocaust. The war also brought about the unification of Ukraine with the West Ukrainian territories of Galicia, Volhynia, North Bukovina, and Carpathian Rus’ (Zakarpattia). The addition of these new territories not only “unified” Ukraine but signaled a “reunification” of all East Slavic territories for the first time in history since the fall of the Kievan Rus’ in the 13th century. The new territories also presented (and continue to present) new complications for Ukraine’s collective identity.

Stepan Bandera, a man regarded throughout much of Ukraine as a wartime collaborator with Nazi Germany and in Western Ukraine (especially Galicia) as a “hero.”

While the vast majority of the people in Central and Southeastern Ukraine view World War II as the “Great Patriotic War” and the Red Army as “saviors,” the view is different in Western Ukraine. In Galicia (centered on the city of Lviv), the Soviet Union is looked on as a “conqueror” or “oppressor” while the OUN (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) and Stepan Bandera who are viewed throughout most of Ukraine as wartime collaborators with the Nazis, are seen as “heroes.” The “hero” view of Bandera also exists but is less prevalent in Volhynia where there are more positive views of the Red Army.

Meanwhile, in North Bukovina and Carpathian Rus’, the view of the Red Army as a “liberator” is much more common and there are reasons for this. North Bukovina’s Slavic population had been repressed under Romania’s chauvinistic government. Meanwhile, Carpathian Rus’ faced attempted Magyarization under Hungarian rule and neglect as part of Czechoslovakia. This, together with the region’s traditional Russophile sentiments, led the locals to welcome inclusion into the Soviet state. Further, the additional factor of the unique Carpatho-Rusyn culture of Carpathian Rus’ also added to the complexity of Ukraine’s collective identity. The region’s absorption into Soviet Ukraine also signaled their official shift in ethno-identification from “Carpatho-Rusyns” to “Ukrainians.” Still, a sense of distinctiveness among the people of Zakarpattia continued to persist.

Following Stalin’s death, Ukraine experienced a very brief renaissance under Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. Khrushchev, who was himself of partial Ukrainian background, even awarded the peninsula of Crimea to Soviet Ukraine, partially out of Slavic sentimentality, partially for economic and irrigation reasons. However, by the 1970s, Ukraine, along with the rest of the USSR, began to fall into stagnation.

Still, Ukrainian speakers co-existed alongside Russian speakers with no problems. Intermarriage and cultural exchange with Russians was commonplace. The only issue with which the Soviet government had to deal was in newly-acquired Galicia, where the insurgent forces of the OUN continued conducting guerrilla operations into the mid-1950s. Yet, overall, Ukraine remained well-integrated into the Soviet Union.

By the time of glasnost, no significant national movement emerged in Ukraine except for the Rukh movement based in Galicia. Generally, most Ukrainians were uninterested in nationalism and more interested in a stable country and a working economy. 72% backed Gorbachev’s New Union Treaty in 1991, though later that year, an overwhelming majority voted in favor of a vaguely-worded referendum on “independence” with no explicit mention of an actual separation from the USSR (which was present, for example, in the wording of Armenia’s referendum on independence).

Post-Soviet Ukraine

Following the Soviet collapse, Ukraine was widely expected to do well as an independent state. Despite the stagnation of the Soviet economy, Ukraine fared as one of the more prosperous Soviet republics. It had an extensive Black Sea coast, rich farmlands, Carpathian Mountain pastures, and heavy industry. However, these expectations faded within the first years of the country’s independence. From the outset, Ukraine faced two challenges: state-building and nation-building. Its corrupt political class was unable to meet both.

In terms of state building, Ukraine had to develop independent institutions and a functional national economy. Kiev was able to develop institutions which were basically successors to the pre-existing Soviet republican institutions. However, Kiev was never able to establish a national economy. Kravchuk, Ukraine’s first post-Soviet president oversaw a corrupt privatization in the 1990s. An oligarchy and a corrupt political elite quickly emerged, stifling Ukraine’s potential development. Poverty, unemployment, organized crime, human trafficking, and other social ills that became characteristic of Ukraine’s post-independence landscape also came to the fore.

Regional politics also remained. Throughout the post-Soviet era, the people of Galicia, the epicenter of Ukrainian nationalism, continued to vote for candidates with nationalist, pro-Western, or anti-Russian credentials. By contrast, the Russian-speaking Southeast (including the Donbas and Crimea) consistently voted for pro-Russian candidates. The more divided, Surzhyk-speaking Central oblasti oscillated between candidates, as did the remote Rusyn-speaking Zakarpattia oblast. Outside of Galicia and Western Ukraine, nationalism generally gained little traction. In the Center and Zakarpattia, it was viewed with indifference and distrust. In the Southeast, it was met with outright hostility.

The Impact of the 2004 Orange Revolution

Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution, backed by Washington and American-based NGOs, was viewed by many Ukrainians as a means of solving the country’s problems and bringing it back on its feet. However, it only exacerbated them. Fundamental issues, such as corruption, remained largely unaddressed. Meanwhile, the pro-Western and nationalist policies of President Viktor Yushchenko enhanced the divisions among Ukrainians. His total affinity for Washington, his push to see Ukraine join the EU and especially NATO, as well as his efforts to rehabilitate and bestow awards on controversial figures like Stepan Bandera, created joy in Western Ukraine, confusion in the Center, and anger in the Southeast. Notably, in 2006, the landing of the US marines in the Crimean city of Feodosiya as part of a US-Ukrainian military exercise prompted major anti-NATO protests from the local population.

The Orange Revolution also intensified these regional divisions on an electoral level. Before the revolution, the politics of Central Ukraine had been more divided, with its oblasti acting as “swing states” and “election spoilers” between pro-Russian and pro-Western candidates. But the Orange Revolution somehow changed this pattern. Though divisions in Central Ukraine persisted and still do persist to this day, the threshold majority began favoring more pro-Western politicians. Coincidental to this development was the rise of Viktor Yanukovych’s Party of Regions (henceforth PoR) which claimed to represent the interests of Russian-speaking Ukrainians and ethnic Russians in Ukraine. In elections, the PoR began to secure the solidly Russian-speaking oblasti from Odessa to the Donbas.

Most striking were the ways in which these new political divisions began to change historical relations between oblasti in Ukraine. A good example is the division that now exists between Sumy and Kharkiv. Historically, these two cities and their oblasti had a long history together, going back to their common foundation in the 17th century as part of the frontier region of Slobozhanshchina (or Sloboda Ukraine). In post-Soviet Ukraine, both the Sumy and Kharkiv oblasti followed each other’s electoral patterns. However, starting with the Orange Revolution, these two oblasti began to diverge from one another. Sumy, despite its Russian-speaking culture and heritage, was the native region of Viktor Yushchenko who became “nationalized” in Galicia. Yet, despite his nationalist ideology, Yushchenko’s place of birth in Russian-speaking Sumy strengthened his credentials in Washington and among American NGOs as “the man who could bring East and West together.” However, as the case of Sumy illustrates, Yushchenko only intensified the divisions. As a result of the Orange Revolution, the Sumy oblast and city began to be carried by pro-Western politicians. Pro-Russian politicians still came close to them in elections, but the overall political orientation began to shift. By contrast, Kharkiv became a solidly pro-Russian PoR oblast.

Superimposed on all of this was the growing geopolitical competition between the United States and Russia for influence in the post-Soviet space. Many commentators warned against the expansion of US influence in the region, particularly with regard to the NATO military alliance. Yet in the 2000s, Washington began to push beyond expanding NATO into Central-East Europe. They also began to look toward the former USSR, particularly the two most strategic ex-Soviet republics: Ukraine and Georgia. The sponsorship by Washington and American NGOs of the Rose and Orange Revolutions in these countries deeply troubled Moscow. The Kremlin subsequently began to throw its support behind the PoR and Yanukovych as the most “pro-Russian” force in the country.

Therefore, the development of divergent political forces domestically within Ukraine, combined with the geopolitical competition between Russia and the West, have effectively set the stage for the present-day conflict in the country. A solution to Ukraine’s protracted crisis can still be found – but it first and foremost requires a ceasefire, humanitarian aid relief for the people of the Donbas, and, most importantly, political will. Moscow has signaled its readiness for such a process.

For more information on Ukraine’s historical, regional, and linguistic dynamics, see my earlier entries: What Is Ukraine? (2 March 2014, updated 15 May 2014), Who Are the Rusyns? (19 April 2014), The Historical Geography of Ukraine (15 May 2014, updated 24 August 2014), and 10 Points on the People of Southeastern Ukraine (21 June 2014).

Donbas Tragedy

Note: An updated and slightly expanded version of this piece was published in The Nation magazine as Is Ukraine on the Brink of Tragedy? on 3 September 2014.

As the conflict in Ukraine’s Donbas (also known as “Donbass” in Russian) continues to rage, there is ongoing debate about what will happen if Kiev manages to reassert its control over the region. To some in Moscow, the defeat of the rebels means the defeat of Russia. They argue that if Kiev succeeds in taking the Donbas, it will mean the whole of Ukraine proper in NATO with possible fighting even in Russian-controlled Crimea. By contrast, Washington’s view is that a victory over the rebels in the Donbas would signal a “victory for democracy” and for Ukraine’s “European choice” (and possibly even “Euro-Atlantic choice”).

Are these narratives accurate? Will Russia really lose out geopolitically if Kiev defeats the rebels? Would this really be a victory for Washington? Would Ukraine become stable and would the defeat of the rebels really signal the start of Ukraine’s “path toward democracy?”

In reality, even if Kiev manages to defeat the rebels and reestablish its control over its rebel oblasti, there will still be many more daunting challenges to face.

First and foremost, the vast majority of Russian-speaking Southeastern Ukrainians from Odessa to Kharkov (many of whom did not even support the rebels) will still view Kiev with distrust and as a “coup government” regardless. Additionally, if Kiev persists with driving through painful IMF-sponsored economic austerity “reforms,” it will turn not only the entire Southeast but also the more mixed areas of Central Ukraine against them. The situation will likely be even more challenging for Kiev in the Donbas itself where civilians have faced near-constant shellings, bombardments, and atrocities. Many of their neighbors, friends, and families have also made the trek to Russia as refugees. According to the UN, close to a million Ukrainians have fled to Russia since the crisis in Ukraine began.

Then there are bombed-out towns like Slavyansk, the remnants of the “anti-terrorist” assault. Kiev will already have difficulty supplying itself and Europe for a long, cold winter. How will they supply a city like Slavyansk where the infrastructure has been virtually bombed into oblivion? It is doubtful that anyone would want to stay in a bombed-out shell of a building for a freezing cold winter, especially a family.

Further, despite the persistence of US State Department officials and the US political elite, the American government can realistically go only so far in supporting the scenario that they helped to create. They will quickly discover that they simply do not have the resources and funds to continue supporting Kiev. Even if they did, those funds would be almost guaranteed to be misused and misspent by Ukraine’s corrupt political elite.

Certainly, for those supporters of Maidan, the reality of the corrupt Ukrainian political elite will come to roost very soon. In addition to painful economic reforms, it is unlikely that there will be any major effort to tackle Ukraine’s massive corruption issue or pay off its astronomical debt. That said, the disappointment with Maidan may well come faster than did the disillusionment with the 2004 Orange Revolution.

Therefore, while it may seem to some in Moscow that a defeat of the Donbas rebels signals the “imminent defeat of Russia,” in reality time is on Russia’s side.

However, then the question becomes: until the realities of the situation begin to set in, how much more suffering will the Ukrainian people have to endure?

After all, the greatest tragedy of the Ukraine crisis is that when future historians look back at all the damage that has been done by this conflict – the deaths, the divided families, the refugees, the destroyed cities, the severed economic links, the ruined diplomatic ties, etc. – they will perhaps wonder, as historians of other unnecessary wars do today: was it really worth it?

Putin and Poroshenko: A Tale of Two Presidents

Updated on 15 March 2015 with newly revealed information on Crimea.

Ukraine’s Petro Poroshenko and Russia’s Vladimir Putin are in a pickle. Both presidents have a crisis on their hands in Ukraine. Both presidents know genuinely how to resolve it: through diplomacy and dialogue. However, the currents of the crisis in Ukraine, and that of history in general, seem to be moving faster than either gentlemen would prefer.

Following his election as Ukraine’s President, the Podolian “Shokoladni Tsar” Poroshenko inherited the so-called “anti-Terrorist operation” from the Yatsenyuk government. Poroshenko seems to want to end the conflict and has vocally sought to reach out to his Russian-speaking compatriots in the Donbas. Yet at the same time, he appears restrained in what he can do, and at times even appears to even endorse the controversial “anti-Terror” campaign that has thus far cost hundreds of lives, including many civilians. There are at least three reasons for this.

One is that the 2004 Orange Revolution constitution was restored in Ukraine, which effectively means that the Ukrainian parliament, the Rada, has more power than Poroshenko. Therefore, by law, Poroshenko is limited in what he can do.

Dmytro Yarosh, leader of the far-right paramilitary organization Right Sector, flanked by two members of the group. Right Sector has actively participated in the controversial “anti-terrorist operation” in the Donbas in which hundreds of civilians have died. (Reuters / David Mdzinarishvili)

The second problem that Poroshenko faces is the fact that the “anti-Terrorist operation” is led by a disparate assortment of groups including Right Sector (Praviy Sektor) and other far-right militants, the Maidan self-defense forces, oligarch-financed militias (effectively “private armies”), and (allegedly) mercenaries from other countries. The regular Ukrainian army, with defections and desertions, has proved to be unreliable for Kiev. Therefore, to “reign in” the rebels, it relies on these “independent” groups and militias. The problem with this strategy is that the latter are truly “independent” and thus it is difficult for Poroshenko to command them to “stop,” even though he is now calling for a cease-fire.

Finally, Poroshenko is under pressure from rival political forces, primarily the Batkivshchyna party and its leader Yulia Tymoshenko, who has threatened to launch “another Maidan” if Poroshenko’s presidency proves to be a disappointment. In a concerning development, the usually pro-Western and liberal Batkivshchyna now appears to be co-opting itself with Ukraine’s nationalists. In fact, since this crisis commenced, nationalism and Russophobia appear to have become increasingly prevalent within the Ukrainian political elite; though it is doubtful that these attitudes reflect the popular sentiment of the vast majority of Ukrainian people.

On the Russian side, Putin is in a no less enviable position. Despite Western and Ukrainian allegations that the Donbas rebels are effectively Russian puppets, the truth is that they are indeed largely comprised of locals. However, they do indeed have supporters and handlers across the border in Russia. These are primarily extremist and nationalist Russian political forces led by fanatical ideologues and writers like Aleksandr Dugin and Aleksandr Prokhanov and fierce commanders like Igor Strelkov. They write for far-right Russians gazetas like “Zavtra,” reenact battles from the 1918-22 Russian Civil War as White Army officers, and like their nationalist Ukrainian counterparts, they too harbor antisemitic sentiments. They dream of forging an authoritarian Eurasian state, a vision that (despite Western rhetoric) is in fact quite different from post-Soviet integration schemes like Putin’s Eurasian Union or similar ideas proposed by Mikhail Gorbachev, Kazakhstan’s Nursultan Nazarbayev, and others in the past.

The Russian nationalists supporting the Donbas rebels are not officially backed by the Russian government. Instead, they are acting out of sheer nationalist zeal. However, hardliners among Russia’s political elite, like Dmitry Rogozin, are putting great pressure on Putin to intervene to support the rebels. For his part, Putin has to balance relations between the hardliners like Rogozin and the more liberal wing of the Kremlin represented by Dmitry Medvedev and other liberals from Putin’s Sobchak days. As I wrote earlier, the hardliners earlier demanded that Putin immediately annex Crimea. The Medvedev group supported a referendum on the issue but ultimately favored caution, arguing that an outright annexation would make relations with the West worse. In the end, Putin ordered a special operation in Crimea in which the troops of the Black Sea Fleet gained control of the peninsula as a so-called “self-defense force.” He also took the position that he would support the final outcome of the Crimean referendum, whatever the result. In the end, the population voted for the incorporation of Crimea into Russia and Putin backed this decision.

This has not occurred with the Donbas and Eastern Ukraine. Despite invoking the rhetoric of “Novorossiya,” Putin has refrained from intervening in Ukraine, a decision that was likely not only influenced by Medvedev and the liberals, but also by other dynamics as well. These include the mere fact that the division between the Russian-speaking oblasti and the mixed Russo-Ukrainian Surzhyk-speaking oblasti in Ukraine is ambiguous. Thus it would be very dangerous for Russia to intervene militarily, if only for this reason. Further, Putin had clear geopolitical objectives in Crimea centered around concerns regarding the Black Sea naval base and potential NATO expansion. There are no such geopolitical concerns for Eastern Ukraine specifically, though in the bigger picture, the fate of Ukraine as a totality is important for Russia geopolitically. That said, while Russia will likely not intervene militarily in Ukraine to support the Donbas rebels, it may lend itself to other initiatives, including establishing a humanitarian corridor. Given the outcry in the Russian public over the atrocities and violence occurring in the Donbas in Kiev’s controversial “anti-terrorist operation,” this may very well happen.

Finally, it must be noted that a major shortcoming and self-defeating factor of the Donbas rebels is their narrow focus. Their ideology is based on Russian nationalism, Orthodoxy, Russian-speakers, the southeastern oblasti of Ukraine, and “Novorossiya” (even though Novorossiya historically did not cover all of the Russian-speaking oblasti). However, this hardly makes for a viable ideology that can attract large numbers of people and that the Kremlin can feel justified in supporting. Such an ideology may find traction in the Donbas where sympathies for Russia run particularly high. However, in the old Sloboda Ukraine (centered on Kharkiv), historic Zaporozhia (centered on Dnepropetrovsk), and the “core” of Novorossiya (cities like Odessa and Nikolayev), the ideology of the rebels has garnered very little traction, even if the population has a strong dislike of the post-Maidan government and disapproves of the atrocities being committed in the so-called “anti-Terrorist operation.” Also, most have no interest in seceding from the Ukrainian state, even though they strongly dislike the current government.

Further, while the majority of the locals in Southeastern Ukraine speak Russian and take their cultural cues from Russia, they still identify as ethnic Ukrainians. Tsarist-era censuses (particularly the 1897 census) attest to the fact that the people of this area largely self-identified as “Malorussians” (i.e., Ukrainians) in Tsarist times. Hence, the people of these oblasti are indeed of Ukrainian origin and are not ethnic Russians who simply adopted the “Ukrainian” ethnonym in the Soviet era. Therefore, unless the rebels think in terms of “Ukraine” as opposed to “the Donbas” or “Novorossiya,” most southeastern Ukrainians will continue to view them with skepticism.

As the Ukraine crisis enters a violent, prolonged military phase, its greatest tragedy is that the people of the Donbas and other regions of Ukraine will continue to suffer in the process, becoming cannon fodder for rival Ukrainian and Russian nationalist visions. Meanwhile, Putin and Poroshenko will continue to remain hostage to events that are unfolding fast. History will proceed, regardless of what either president has to say about it.

Who are the Donbas Rebels?

Updated on 15 March 2015 with newly revealed information on Crimea.

As I have written previously, based on the available evidence, I have concluded that most of the Donbas rebels are indeed locals. At the same time, I also believe that they are being encouraged by Russian nationalists from Russia, such as Igor Strelkov. These nationalists are acting in a private capacity to not only assist but also encourage the rebels. It is important to note that they are not supported in their endeavors by official Moscow.

However, the hardline faction of the Russian political elite, led by Dmitry Rogozin, wants Putin to intervene in Eastern Ukraine to support the rebels. They took a similar position on Crimea. Following ouster of Yanukovych from power in Kiev, a debate ensued in Moscow on the fate of Crimea. Concerns regarding NATO expansion in Ukraine, the influence of the far-right in the new Kiev government, and the potential effort by the new Kiev government to expel the Russian Black Sea Fleet from Sevastopol prompted the debate over the peninsula’s status. Such fears were not unfounded as many in the Kiev government supported Ukrainian NATO membership, while others sought to cancel Russia’s lease on the base – and still others on the far-right (particularly Oleh Tyahnybok and Svoboda) wanted to abolish Crimea’s autonomy entirely.

The hardliners demanded immediate annexation, arguing that you either “take Crimea today” or “fight there tomorrow.” At the same time, the more liberal political wing in Moscow (represented by Dmitry Medvedev and others from Putin’s St. Petersburg Sobchak days) was opposed to annexing Crimea outright. They favored a referendum on the issue, but preferred to delay a final decision on the matter and use Crimea as a “bargaining chip” to ensure the presence of the Sevastopol base and to ensure that Ukraine does not join NATO. Additionally, they argued, if Russia were to “reunite” with Crimea right away, it would make relations with the West even worse.

Putin ordered an emergency opinion poll during this time that showed that the vast majority of Crimeans wanted to join Russia. Weighing all options, Putin ultimately decided to support the pro-Russian movement in Crimea through a special operation, using the troops from the Black Sea Fleet to gain control of the peninsula as a so-called “self-defense force,” starting on 27 February 2014.

Putin also took the position that he would favor the outcome of the referendum, whatever the final result. As he said in a new documentary on Crimea that was aired on Russian television on 15 March 2015, his “final goal was to allow the people express their wishes on how they want to live. I decided for myself: what the people want will happen. If they want greater autonomy with some extra rights within Ukraine, so be it. If they decide otherwise, we cannot fail them.” The referendum was then organized in which the majority of the voters cast their ballots in favor of reunification with Russia. The rest is history.

The hardliners seek to convince Putin to take a similar position in Eastern Ukraine. However, the potential of intervening there is far more dangerous. Primarily, the linguistic demarcation between Russian-speaking Southeastern Ukraine and Surzhyk-speaking Central Ukraine is very blurred. Thus a Russian intervention would only make the situation more dangerous. Given this and other factors, Putin has not did not yielded to the pressure of the hardliners to intervene, even after a referendum was organized in the Donbas. In this regard, the more liberal St. Petersburg faction in the Kremlin, led by Medvedev and others, has been successful in persuading Putin not to intervene. The most that Putin conceded to the hardliners with regard to Eastern Ukraine was his invoking of historic “Novorossiya.” However, even here, Putin has recently moved away from making such statements and has made attempts to clarify his use of that term to stress that Moscow is not seeking territorial claims on Ukraine.

The Historical Geography of Ukraine: An Overview

Updated and expanded on 24 August and 2 September 2014 with additional information.

Given all the discussion about Ukraine’s regional divisions, I thought that it might be useful for observers if I gave a quick overview of the historical geography of Ukraine by the larger regions within the country. This may help sort out the uses and abuses of history in the ongoing Ukraine crisis.

Western Ukraine:

Galicia:

- Contemporary regions: Lviv, Ternopil, and Ivano-Frankivsk oblasti

- Major cities and towns: Lviv, Ternopil, and Ivano-Frankivsk

- Notes: Part of Austria-Hungary and then interwar Poland before becoming part of the USSR. It must be emphasized that this region was never part of the Russian Empire, though it was a principality of the old Kievan Rus’.

Volhynia:

- Contemporary area: Volhyn and Rivne oblasti

- Major cities and towns: Lutsk and Rivne

- Notes: Part of the Russian Empire and then interwar Poland before becoming part of the USSR.

Northern Bukovina and Northern Bessarabia:

- Contemporary area: Chernvisti oblast

- Major cities and towns: Chernvisti and Khotyn

- Notes: Though geographically part of the West, this region has voting and linguistic patterns that are similar those found in Central Ukraine. The locals largely speak the mixed Russian-Ukrainian language Surzhyk (spoken by most in Central Ukraine) and elections here are very close. There is also a large Romanian minority (about 20% of the total population) which plays an additional factor in the region’s politics. The area was part of the interwar Kingdom of Romania and Romanian nationalists in Bucharest still claim the region as rightfully their’s.

Carpathian Rus’, also known as Subcarpathian Rus’ or Transcarpathian Rus’:

- Contemporary area: Zakarpattia oblast

- Major cities and towns: Uzhgorod, Mukachevo, Khust, and Rakhiv

- Notes: Part of the Kingdom of Hungary within Austria-Hungary and then part of interwar Czechoslovakia before becoming part of the USSR. The homeland of the Carpatho-Rusyns, Carpathian Rus’ is sometimes considered its own distinct region due to its unique ethnic, linguistic, and cultural character. There is also a 12% Hungarian minority in this region. Hungarian nationalists in Budapest who refuse to recognize the 1920 Treaty of Trianon still claim the region as rightfully their’s.

Central Ukraine:

Dnieper Ukraine:

- Contemporary area: Most of the Central oblasti of Ukraine, particularly the Kiev, Cherkasy, Poltava, and Zhytomyr oblasti.

- Major cities and towns: Kiev, Cherkasy, Poltava, and Zhytomyr

Podolia:

- Contemporary area: All of the Vinnitsyia and Khmelnytskyi oblasti, with the southwesternmost parts of the Kiev oblast, the westernmost parts of the Cherkasy oblast, the northern portions of the Odessa oblast, and the northern parts of the breakaway region of Transnistria in Moldova.

- Major cities and towns: Vinnitsyia, Khmelnytskyi, Kamianets-Podilskyi, and Rybnitsa

Polesia:

- Contemporary area: Northern parts of the Zhytomyr, Kiev, Chernihiv, and Sumy oblasti, sometimes including the northern parts of Volhynia too.

- Major cities and towns: Chernihiv, Shostka, Nizhyn, and Korosten

Southeastern Ukraine:

Zaporozhia:

- Contemporary area: The core territory of this region encompassed the Dnipropetrovsk oblast, the northern portions of the Zaporozhia oblast, and virtually all of the Central Ukrainian oblast of Kirovograd. Additionally, it included the very small southernmost portion of the Poltava oblast south of the Dnieper River, around the southern side of the industrial city of Kremenchuk. Zaporozhia also extended east to include parts of the Kharkiv, Donetsk and Luhansk oblasti and south to include the northernmost portions of the Nikolayev and Kherson oblasti.

- Major cities and towns: Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporozhia, Kryvyi Rih, and Kirovograd

- Notes: The word “porozh” in Ukrainian and Russian indicates “rapids” so the name literally means “land beyond the rapids” (referring to the rapids of the river Dnieper).

Sloboda Ukraine (Free Ukraine), also known as Sloboda Zemlya (Free Land) or Slobozhanshchina:

- Contemporary area: Almost all of the Kharkiv oblast, except for the southernmost parts. Also included were the southern portions of the Central Ukrainian Sumy oblast, the northernmost portions of the Donetsk oblast, and the areas of the Luhansk oblast north of the Seversky Donets river.

- Major cities and towns: Kharkiv, Sumy, Izyum, and Starobilsk

- Notes: The Tsarist-era Kharkov guberniya approximately corresponds to the boundaries of Sloboda Ukraine. According to the Tsarist census of 1897, the guberniya’s population was majority ethnic “Little Russian” (i.e., Ukrainian). Also, until 1939, the city of Sumy and the southern portions of the modern-day Sumy oblast were part of the Soviet-era Kharkov oblast.

The Donbas:

- Contemporary area: The Donetsk and Luhansk oblasti (also the breakaway “People’s Republics” of Donetsk and Luhansk).

- Major cities and towns: Donetsk, Luhansk, Mariupol, Slavyansk, and Kramatorsk

- Notes: The name is short for “Donets Basin.” In Tsarist times, the Donbas region was administratively divided. The northern portions of both oblasti were part of the Kharkov guberniya (the historic Sloboda Ukraine), while their western portions were part of the Yekaterinoslav guberniya (the eastern part of historic Novorossiya), and their eastern portions were part of the Don Host Oblast which also included significant portions of Southern Russia. Due to the latter fact, some might argue that the eastern Donbas was once “part of Russia.” However, such an argument is problematic because, in this region, the distinction between what is “Russian” and what is “Ukrainian” becomes increasingly blurred. For instance, this area between Russia and Ukraine is so demographically mixed that some Ukrainians might conversely claim parts of Southern Russia as “Ukrainian.” The blurriness is compounded by the fact that the Cossacks who historically lived in these areas were not from an exclusive national group. They were both Russians and Ukrainians.

Crimea, also known as Taurida:

- Contemporary area: The Republic of Crimea and the Federal City of Sevastopol administered by Russia, the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the City of Sevastopol, claimed by Ukraine.

- Major cities and towns: Sevastopol, Simferopol, Kerch, Feodosiya, and Yalta

- Notes: In addition to the Crimean peninsula, the Tsarist-era Taurida guberniya also included significant portions of the modern Kherson and Zaporozhia oblasti in contemporary Ukraine. However, this “mainland” part of the guberniya (also considered to be part of “Novorossiya proper”) significantly differed demographically from the peninsula. According to the 1897 Tsarist census, the mainland’s population was primarily “Little Russian” (Ukrainian) with a significant “Great Russian” (ethnic Russian) minority, while the population of the peninsula was largely “Great Russian” and Tatar with a significant Ukrainian minority and additional ethnic minorities of Germans, Jews, Bulgarians, Greeks, Armenians, Poles, and others.

The Budzhak:

- Contemporary area: Portion of the Odessa oblast situated south of Moldova, east of Romania and the Danube, and west of the Dniester, on the Black Sea coast.

- Major cities and towns: Izmail and Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi (Akkerman)

- Notes: Historically the southernmost part of Bessarabia, this region was part of the interwar Kingdom of Romania until it was annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940. In Soviet Ukraine, it was administered as the Akkerman oblast, later renamed the Izmail oblast. In 1954, the oblast was abolished and incorporated into the Odessa oblast. A multiethnic region, the Budzhak is majority Ukrainian with substantial Bulgarian, Russian, Romanian, and Gagauz minorities. The name “Budzhak” is derived from the Turkish word “bucak,” meaning “district” or “corner.”

The Yedisan:

- Contemporary area: The southern portions of Transnistria and the Odessa oblast (excluding the Budzhak), the southern portion of the Nikolayev oblast, and the southwestern portion of the Kherson oblast.

- Major cities and towns: Odessa, Nikolayev, and Tiraspol

- Notes: The name “Yedisan” (alternatively transliterated as “Edisan” or “Jedisan”) is derived from a nomadic Nogai Turkic tribe who once inhabited this area. It literally means “seven titles” referring to seven different subdivisions among the tribe. In the 18th century, the region was incorporated into Imperial Russia by Catherine the Great as part of Novorossiya and settled by Ukrainians (Malorussians), Russians, and others. The area was also known as “Ochakov Tartary” after the historic fortress of Ochakov located in the contemporary Nikolayev oblast.

Novorossiya (New Russia):

- Contemporary area: The Nikolayev and Kherson oblasti, the southern portions of Transnistria and the Odessa oblast (excluding the Budzhak), the southern part of the Zaporozhia oblast, the southeasternmost area of the Kharkiv oblast, the Western half of the Donbas (including the cities of Donetsk and Luhansk), and most of the historical region of Zaporozhia. Novorossiya also occasionally included Bessarabia (Moldova proper with the Budzhak region of the Odessa oblast), Crimea, and the Don Host Oblast (the eastern half of the Donbas and significant portions of Southern Russia).

- Major cities and towns: Odessa, Nikolayev, Kherson, Tiraspol, and Berdyansk

- Notes: It must be emphasized that, with the exception of its southeasternmost area, much of the territory of the modern-day Kharkiv oblast was not part of Novorossiya. Further the majority population of the core territory of Novorossiya (Odessa, Nikolayev, Kherson, southern Transnistria, western Donbas, and historic Zaporozhia) in the 1897 Tsarist census were identified as ethnic “Little Russians” (Ukrainians) with significant minorities of “Great Russians” (ethnic Russians) and, in the Odessa area, Jews. Consequently, the idea of making this region a part of Soviet Ukraine was logical from a geographic and ethnographic standpoint. Thus, it must be emphasized that the assignment of these territories was not a “great mistake” by the Bolsheviks as Russian President Vladimir Putin, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin and others have been claiming. Indeed, it is likely that Putin is advancing the Novorossiya claim to placate hardliners like Rogozin in the Kremlin who want to invade Southeastern Ukraine and are attempting to use historical revisionism to show that the region is “another Crimea” in order to justify such actions. However, no invasion can be justified and would be a disaster for both Russia and Ukraine.

Novaya Serbiya (New Serbia):

- Contemporary area: Northern portions of the Kirovograd oblast, with some adjoining areas of the neighboring Cherkasy, Poltava, and Dnipropetrovsk oblasti.

- Major cities and towns: Novomyrgorod

- Notes: Founded by Tsarist Russia as a military frontier with Poland in the 1750s populated by Serbs, Montenegrins, Romanians, and others from Habsburg Austria (hence the name). The territory was later abolished in 1764 and incorporated into Novorossiya.

Slavo-Serbiya (Slavo-Serbia):

- Contemporary area: Border regions between the modern-day Donetsk and Luhansk oblasti.

- Major cities and towns: Artemivsk (Bakhmut)

- Notes: Founded by Tsarist Russia as a refuge for Serbs, Montenegrins, Romanians, Bulgarians, Hungarians, Greeks, and others. The territory was later abolished in 1764 and incorporated into Novorossiya.

For more information on Ukraine’s diverse regional divisions, see my earlier post, What is Ukraine? from March here, now updated and expanded to include the latest information about Ukraine.