As the Ukraine crisis continues, there are debates emerging with regard to the relationship between Russians and Ukrainians, in language, culture, and history.

The vast majority of ordinary Russians view Ukrainians, though linguistically distinct, as being a fraternal East Slavic nation, closely bound to Russia by culture, history, and intermarriage. They further assert that Ukraine is an integral part of Russian civilization, owing to the particularly special significance of Kiev to both Russians and Ukrainians. More nationalistic Russians go even further and claim that Ukraine is merely a “concept” and that the people known as “Ukrainians” are merely an extension of the Russian nation who speak a dialect of Russian.

Some Ukrainians, particularly in the Central part of the country, would sympathize with the argument that Russians and Ukrainians are a fraternal people. In the Russian-speaking Southeast this would be further elevated to Russians and Ukrainians being “the same people.” However, as one might imagine, the nationalist discourse in Western Ukraine, particularly Galicia, is radically different. To Ukrainian nationalists, Ukrainians are “completely different” from the Russians. They have they own culture, language and history which they believe is “entirely disconnected” from anything to do with the Russians. Some more extreme Ukrainian nationalists even claim that the Ukrainian language is not only distinct from Russian, but also distinct among all Slavic or even Indo-European languages as well.

Of course, the truth exists somewhere in-between these conflicting narratives. It is true that Ukrainians do speak their own language and that there are aspects of Ukrainian culture that are indeed unique to Ukrainians. However, it is also true that Kiev is the common point of origin for all East Slavs including Ukrainians and Russians; that at one time in their common history, they used to speak the same language (Old East Slavic); and that the contemporary Ukrainian and Russian languages (though not exactly the same) are indeed very similar. It is also true that the Ukrainians and Russians have much in common in terms of culture, and they have both had a major impact on one another. Examples of this cultural exchange include the squat-and-kick prisyadka dance move and the beet soup borscht, both of Ukrainian origin but deeply influential in Russian culture. Nikolai Gogol was a famous Russian-language author of Ukrainian origin who often included Ukrainian themes in his writings, e.g., Taras Bulba. The great Russian painter Ilya Repin, though himself an ethnic Russian, was born in Ukraine and also included many Ukrainian themes in his work, signaling his great love for his fellow East Slav brothers.

Intermarriage is also a major component of the Russo-Ukrainian relationship. Nikita Khrushchev and Mikhail Gorbachev were both products of mixed Russo-Ukrainian parentage; their wives, Nina Kukharchuk and Raisa Titarenko, were both fully Ukrainian. Another former leader, Lenoid Brezhnev, was also of mixed Russian-Ukrainian heritage while another, Konstantin Chernenko, came from a Russified Ukrainian family. In music, the famous Russian rock star Yuri Shevchuck is Ukrainian and the Bessarabian-born Russian tango singer of the 1930s Pyotr Leschenko was also of Ukrainian background. Additionally, the dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, and the great Soviet rocket engineer Sergei Korolyov were all born to mixed Russian-Ukrainian parents.

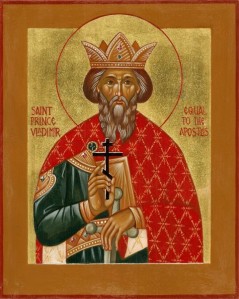

Kievan ruler Vladimir the Great was baptized at Khersones (in modern-day Sevastopol) and converted the Kievan Rus’ to Christianity in the 10th century. Vladimir is widely revered by all East Slavs (including Russians and Ukrainians) to this day.

Rus’, Malorussia, Ukraine, and the Politics of Identity

Another aspect of the very close relationship between the Russians and the Ukrainians is the historical development of the identity of the Ukrainian people. At one point, all of the East Slavs (Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Carpatho-Rusyns) used to comprise a single people – the people of the Rus’ – who used to speak a single language known as Old East Slavic. Their faith was Orthodox Christianity. The only exception to this were the Kievan territories of Galicia and Volhynia. Forming the westernmost regions of the old Rus’, Catholic and Polish influence was very strong in these areas, particularly Galicia, and their princely families even intermarried with nearby Catholic Polish and Hungarian houses. Significantly, while there was a distrust of Catholicism in the other Rus’ territories further east, in Galicia and Volhynia, Catholic and Western ideas were welcomed and fully embraced. This early cultural division would later play a role in Ukraine’s regional identity differences centuries later.

Another key factor was language. In the 13th century, the Kievan Rus’ fell into decline and became subjected to the Mongol invasions. Its western principalities (largely correspondent to much of modern-day Central Ukraine and Belarus) were absorbed by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which later unified with the Kingdom of Poland at the Union of Lublin in 1569, forming the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The gradual “break-up” of the single Old East Slavic language into several different languages – Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Carpatho-Rusyn – occurred during this period. Yet, even into the early 20th century, many of these East Slavs still self-identified as “Rusyni” and spoke a language which they called “Rusynski,” both referring to the old Rus’ state.

Foreign rule further created a new dimension to the situation which involved religion. Rus’ lands under Mongol rule remained free to worship and practice their Orthodox Christian faith. By comparison, in those Rus’ lands under Polish-Lithuanian rule, Orthodoxy was at first tolerated. Later, however, the separateness in faith concerned the Polish monarchs as the Orthodox locals of the historic Rus’ lands saw their affinity not with Catholic Poland or Western Europe but with the world of Russian Orthodoxy. As such, Orthodox Christians were persecuted under Polish rule until in 1595, in exchange for an end to this persecution, the Orthodox clergy of the Polish-ruled lands agreed to the Union of Brest, forming the Ukrainian Greek Catholic (or Uniate) Church. However, in subsequent centuries, as the Russian Tsars later reclaimed the old western Rus’ lands from Poland-Lithuania in the 18th century Partitions of Poland, the Orthodox faith was reintroduced. Significantly, in the Partitions, the Habsburg monarchy in Austria acquired the Catholic- and Western-leaning region of Galicia.

Additionally, an entirely separate situation existed further west in the region of Carpathian Rus’ (Zakarpattia). This distant western region was a borderland frontier area at the time of Kievan Rus’. It fluctuated between the control of Orthodox East Slav Kievan rulers to the north and east and Magyar (Hungarian) Catholic rulers to the south and west. With the fall of Kievan Rus’, this Carpathian territory fell under the complete control of the Hungarian monarchs. Overtime, the close proximity of the Catholic Slovak and Magyar populations combined with the area’s separateness from the other historic Rus’ lands due to the Carpathian Mountains led it to develop its own entirely distinct identity and language (Carpatho-Rusyn). This difference was reinforced with the Union of Uzhgorod in 1646 in which the Orthodox Rusyns joined the Catholic Church as part of the Byzantine rite, forming the separate Byzantine Ruthenian Catholic Church.

As mentioned earlier, the Russian Tsars later reclaimed much of the old western Kievan Rus’ territories in modern-day Ukraine in Belarus during the Partitions of Poland in the 18th century. Orthodoxy was also reintroduced in these regions. The “Rusyni” identity of old persisted among the locals and, during the 19th century, two rival nation-building projects on the territory of contemporary Ukraine sought to supplant this old “Rusyni” identity with a new identity. One was the Malorussian (“Little Russian”) identity, with the name “Little Russia” derivative from old Byzantine maps referring to modern Ukraine as “Lesser Rus'” or “Rus’ Minor.” The Malorussian project claimed that modern Ukraine was a natural extension of the Russian nation. In the Malorussian view, the Ukrainian language that developed from the break-up of Old East Slavic had to be supplanted by a common standard language. In their view, this was to be Russian, a language seen by Malorussian activists as the “successor” of Old East Slavic. Nikolai Gogol, an ethnic Ukrainian who wrote in Russian, was among those who favored Malorussianism.

Opposing Malorussianism, was Ukrainianism. Ukrainianism postulated that the East Slavic language that developed in Ukraine signified the development of an entirely separate ethnic identity, independent of other East Slavs. They called their nation “Ukraine,” a name that like “Malorussia” developed from cartographic toponyms and has been literally translated as “borderland.” Ukrainianists emphasized the unique and distinct culture of the people of the area above all else, with a special emphasis on language and culture. Of course, this did not exclude those who viewed themselves as “Ukrainian” but also saw Russia as a fraternal East Slavic nation nonetheless. The writer Taras Shevchenko is perhaps best representative of the “Ukrainianist” group, writing almost exclusively in the Ukrainian language, though occasionally writing in Russian as well.

Of these movements, Malorussianism was favored by the Tsars who regarded themselves as the legitimate successors to the rulers of the old Kievan Rus’. Consequently, the Malorussianist policies of official Petersburg should be viewed not within the context of an empire attempting to force an assimilation on a “conquered” people, but rather as part of a nation-building project or as part of the great “reunification of Old Rus'” and “gathering of the Russian lands” as the Tsars saw it.

A similar national project was also taking place in Italy, which had just been unified under the leadership of Giuseppe Garibaldi. There, the Italian language, based on Tuscan and the Central Italian dialects, was to become the literary standard. However, in the southern island of Sicily, the locals spoke their own Romance language Sicilian, related to Italian but also distinct in its own right. In Rome, the king regarded Sicilian just as the Tsar regarded Ukrainian, as a backward provincial dialect which, with the expansion of education and literacy, would be eventually supplanted by “clean Italian” or in the Tsar’s case, “clean Russian.” Indeed, like Ukrainian, Sicilian developed distinct from other languages in Italy by virtue of its geographic separation from the mainland and historical invasions of the island by Greeks, Arabs, Normans, Germans, Spanish, and others. Yet Sicily was viewed by Italianist advocates as an integral and historical part of Italy, just as Ukraine was regarded as an integral and historical part of Russia by the educated class, the bourgeoisie, and the aristocracy.

An additional development to all of this was the emergence of three new historical territories overtime. They included Zaporozhia which established itself in the “wild fields” south of Polish-ruled territory in the 15th and 16th centuries. In this region, rebellious Orthodox Christian Cossacks fought against the Polish monarchs. Then, in the 17th century, the area of Slobozhanshchina (or Sloboda Ukraine) emerged around the cities of Kharkiv and Sumy. Finally, in the 18th and 19th centuries, the area of Novorossiya was formed along the Black Sea after the Russian Tsars had finally succeeded in taking Ottoman-held territory along the coast. In all of these regions, Ukrainian (or Malorussian) populations played primary roles in their historical formation and settlement. Further, in all three of these regions, Orthodoxy was the primary faith.

The Malorussian-Ukrainian debate also took place across the border in the Austro-Hungarian-ruled East Slavic territories of Galicia, North Bukovina (Chernivsti), and Carpathian Rus’. There, the debate existed between Ukrainianists and Russophiles (effectively Malorussian activists under a different name). It became even more complex in Carpathian Rus’ ruled under the the Hungarian realm of the dual monarchy, between Ukrainianists, Russophiles, and Rusynists (those who chose to self-identify as Rusyn or Carpatho-Rusyn). In Galicia, where Catholic influence of both the direct Roman Catholic and Uniate strands remained strong, the debate was eventually won by the Ukrainianists. However, in Carpathian Rus’, the debate over ethnic identity still persists to this day. Notably, during this period, many people from these Austro-Hungarian-controlled territories (particularly Galicia and Carpathian Rus’) also emigrated further west in search of opportunity. They arrived in the United States and Canada, establishing the core of what would become the contemporary Ukrainian and Carpatho-Rusyn diasporas of today.

National Identity in the Soviet Era

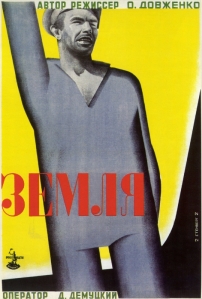

Original avant-garde poster for Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930). The film is perhaps Dovzhenko’s best-known work and it is part three of the director’s “Ukrainian trilogy” which also included Zvenigora (1928) and Arsenal (1929).

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, the civil war in Ukraine of 1917-21, and the establishment of the USSR, Ukrainianism as a movement won out over Malorussianism. In the 1920s, the new Soviet government undertook a “Ukrainization” policy in the newly-declared Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, as part of its broader nativization or korenizatsiya (коренизация) policy toward nationalities, by promoting and advancing the Ukrainian literary language. This had the effect of encouraging a major cultural and literary renaissance in Ukraine during the NEP that many Ukrainians still fondly remember today. The advent of new art forms, like film, helped advance this renaissance, in which the great Ukrainian filmmaker Aleksandr Dovzhenko played a leading role. A pioneer of early Soviet film, Dovzhenko is credited for not only his contributions to the development of Ukrainian cinema but also for Soviet and Russian cinema overall.

The Ukrainization policies were abruptly halted in the 1930s under Stalin whose NKVD purged the republic of real or perceived nationalists, “kulaki,” and “enemies of the people.” Yet, it should be noted that Stalin was not interested in the Malorussian-Ukrainian identity debate, but more concerned with strengthening his position throughout the entire USSR, and to this end he purged writers and intellectuals in all Soviet republics.

Compounding all of this was the terrible Soviet famine of the early 1930s. The famine hit Ukraine very hard and some Ukrainian nationalist historians even go so far as to assert that what happened was a deliberate attempt at genocide against the Ukrainian people by the Soviet government. However, this fails to take into account the fact that the famine also affected many non-Ukrainians too, including Germans, Poles, Jews, and Russians. Likewise, the famine also hit southern Russia and northern Kazakhstan, two other major cereal-producing regions of the Soviet Union, very hard. Among those who witnessed the starvation was a young Mikhail Gorbachev, a native of southern Russia, who personally experienced the horrors of the terrible famine first-hand. It affected his own family and killed off half of his village.

Millions starved to death in this cruel campaign of forced collectivization and suppression of the so-called “kulaki.” Yet, Western correspondents like Walter Duranty disguised the facts while Stalin and Soviet officials claimed that the campaign had made the “eternally happy” people of the Soviet agricultural heartland “dizzy with success.” Overall, ethnicity meant little to Stalin. Nobody was safe from the terror of the vozhd. He was an equal-opportunity mass murderer.

The Soviet era also saw the rise of industrialization. The heavily industrial coal-mining region of the Donbas (Donets Basin), centered on the cities of Donetsk (also known as Yuzovka or Stalino) and Luhansk (also known as Voroshilovgrad) really emerged during this period. Prior to this, the Donbas had been an area with a mixed Ukrainian and Russian Cossack population divided between historical Sloboda Ukraine, Novorossiya, and the Don Cossack Host. The Soviet era firmly established the Donbas as a unique region in its own right, a truly working-class “Soviet” region where Russian was the primary language. It was in this area that, during the Stalin era, Aleksei Stakhanov and the Stakhanovite movement emerged.

World War II left an indelible mark on Ukraine. In the war, most Ukrainians fought alongside the Russians against the onslaught of the Nazi German war machine. Many Ukrainian villagers in present-day Central and Southeastern Ukraine experienced violent atrocities at the hands of the hated Nazi invader and the country’s sizeable and historically significant Jewish community was decimated by the Holocaust. The war also brought about the unification of Ukraine with the West Ukrainian territories of Galicia, Volhynia, North Bukovina, and Carpathian Rus’ (Zakarpattia). The addition of these new territories not only “unified” Ukraine but signaled a “reunification” of all East Slavic territories for the first time in history since the fall of the Kievan Rus’ in the 13th century. The new territories also presented (and continue to present) new complications for Ukraine’s collective identity.

Stepan Bandera, a man regarded throughout much of Ukraine as a wartime collaborator with Nazi Germany and in Western Ukraine (especially Galicia) as a “hero.”

While the vast majority of the people in Central and Southeastern Ukraine view World War II as the “Great Patriotic War” and the Red Army as “saviors,” the view is different in Western Ukraine. In Galicia (centered on the city of Lviv), the Soviet Union is looked on as a “conqueror” or “oppressor” while the OUN (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) and Stepan Bandera who are viewed throughout most of Ukraine as wartime collaborators with the Nazis, are seen as “heroes.” The “hero” view of Bandera also exists but is less prevalent in Volhynia where there are more positive views of the Red Army.

Meanwhile, in North Bukovina and Carpathian Rus’, the view of the Red Army as a “liberator” is much more common and there are reasons for this. North Bukovina’s Slavic population had been repressed under Romania’s chauvinistic government. Meanwhile, Carpathian Rus’ faced attempted Magyarization under Hungarian rule and neglect as part of Czechoslovakia. This, together with the region’s traditional Russophile sentiments, led the locals to welcome inclusion into the Soviet state. Further, the additional factor of the unique Carpatho-Rusyn culture of Carpathian Rus’ also added to the complexity of Ukraine’s collective identity. The region’s absorption into Soviet Ukraine also signaled their official shift in ethno-identification from “Carpatho-Rusyns” to “Ukrainians.” Still, a sense of distinctiveness among the people of Zakarpattia continued to persist.

Following Stalin’s death, Ukraine experienced a very brief renaissance under Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. Khrushchev, who was himself of partial Ukrainian background, even awarded the peninsula of Crimea to Soviet Ukraine, partially out of Slavic sentimentality, partially for economic and irrigation reasons. However, by the 1970s, Ukraine, along with the rest of the USSR, began to fall into stagnation.

Still, Ukrainian speakers co-existed alongside Russian speakers with no problems. Intermarriage and cultural exchange with Russians was commonplace. The only issue with which the Soviet government had to deal was in newly-acquired Galicia, where the insurgent forces of the OUN continued conducting guerrilla operations into the mid-1950s. Yet, overall, Ukraine remained well-integrated into the Soviet Union.

By the time of glasnost, no significant national movement emerged in Ukraine except for the Rukh movement based in Galicia. Generally, most Ukrainians were uninterested in nationalism and more interested in a stable country and a working economy. 72% backed Gorbachev’s New Union Treaty in 1991, though later that year, an overwhelming majority voted in favor of a vaguely-worded referendum on “independence” with no explicit mention of an actual separation from the USSR (which was present, for example, in the wording of Armenia’s referendum on independence).

Post-Soviet Ukraine

Following the Soviet collapse, Ukraine was widely expected to do well as an independent state. Despite the stagnation of the Soviet economy, Ukraine fared as one of the more prosperous Soviet republics. It had an extensive Black Sea coast, rich farmlands, Carpathian Mountain pastures, and heavy industry. However, these expectations faded within the first years of the country’s independence. From the outset, Ukraine faced two challenges: state-building and nation-building. Its corrupt political class was unable to meet both.

In terms of state building, Ukraine had to develop independent institutions and a functional national economy. Kiev was able to develop institutions which were basically successors to the pre-existing Soviet republican institutions. However, Kiev was never able to establish a national economy. Kravchuk, Ukraine’s first post-Soviet president oversaw a corrupt privatization in the 1990s. An oligarchy and a corrupt political elite quickly emerged, stifling Ukraine’s potential development. Poverty, unemployment, organized crime, human trafficking, and other social ills that became characteristic of Ukraine’s post-independence landscape also came to the fore.

Regional politics also remained. Throughout the post-Soviet era, the people of Galicia, the epicenter of Ukrainian nationalism, continued to vote for candidates with nationalist, pro-Western, or anti-Russian credentials. By contrast, the Russian-speaking Southeast (including the Donbas and Crimea) consistently voted for pro-Russian candidates. The more divided, Surzhyk-speaking Central oblasti oscillated between candidates, as did the remote Rusyn-speaking Zakarpattia oblast. Outside of Galicia and Western Ukraine, nationalism generally gained little traction. In the Center and Zakarpattia, it was viewed with indifference and distrust. In the Southeast, it was met with outright hostility.

The Impact of the 2004 Orange Revolution

Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution, backed by Washington and American-based NGOs, was viewed by many Ukrainians as a means of solving the country’s problems and bringing it back on its feet. However, it only exacerbated them. Fundamental issues, such as corruption, remained largely unaddressed. Meanwhile, the pro-Western and nationalist policies of President Viktor Yushchenko enhanced the divisions among Ukrainians. His total affinity for Washington, his push to see Ukraine join the EU and especially NATO, as well as his efforts to rehabilitate and bestow awards on controversial figures like Stepan Bandera, created joy in Western Ukraine, confusion in the Center, and anger in the Southeast. Notably, in 2006, the landing of the US marines in the Crimean city of Feodosiya as part of a US-Ukrainian military exercise prompted major anti-NATO protests from the local population.

The Orange Revolution also intensified these regional divisions on an electoral level. Before the revolution, the politics of Central Ukraine had been more divided, with its oblasti acting as “swing states” and “election spoilers” between pro-Russian and pro-Western candidates. But the Orange Revolution somehow changed this pattern. Though divisions in Central Ukraine persisted and still do persist to this day, the threshold majority began favoring more pro-Western politicians. Coincidental to this development was the rise of Viktor Yanukovych’s Party of Regions (henceforth PoR) which claimed to represent the interests of Russian-speaking Ukrainians and ethnic Russians in Ukraine. In elections, the PoR began to secure the solidly Russian-speaking oblasti from Odessa to the Donbas.

Most striking were the ways in which these new political divisions began to change historical relations between oblasti in Ukraine. A good example is the division that now exists between Sumy and Kharkiv. Historically, these two cities and their oblasti had a long history together, going back to their common foundation in the 17th century as part of the frontier region of Slobozhanshchina (or Sloboda Ukraine). In post-Soviet Ukraine, both the Sumy and Kharkiv oblasti followed each other’s electoral patterns. However, starting with the Orange Revolution, these two oblasti began to diverge from one another. Sumy, despite its Russian-speaking culture and heritage, was the native region of Viktor Yushchenko who became “nationalized” in Galicia. Yet, despite his nationalist ideology, Yushchenko’s place of birth in Russian-speaking Sumy strengthened his credentials in Washington and among American NGOs as “the man who could bring East and West together.” However, as the case of Sumy illustrates, Yushchenko only intensified the divisions. As a result of the Orange Revolution, the Sumy oblast and city began to be carried by pro-Western politicians. Pro-Russian politicians still came close to them in elections, but the overall political orientation began to shift. By contrast, Kharkiv became a solidly pro-Russian PoR oblast.

Superimposed on all of this was the growing geopolitical competition between the United States and Russia for influence in the post-Soviet space. Many commentators warned against the expansion of US influence in the region, particularly with regard to the NATO military alliance. Yet in the 2000s, Washington began to push beyond expanding NATO into Central-East Europe. They also began to look toward the former USSR, particularly the two most strategic ex-Soviet republics: Ukraine and Georgia. The sponsorship by Washington and American NGOs of the Rose and Orange Revolutions in these countries deeply troubled Moscow. The Kremlin subsequently began to throw its support behind the PoR and Yanukovych as the most “pro-Russian” force in the country.

Therefore, the development of divergent political forces domestically within Ukraine, combined with the geopolitical competition between Russia and the West, have effectively set the stage for the present-day conflict in the country. A solution to Ukraine’s protracted crisis can still be found – but it first and foremost requires a ceasefire, humanitarian aid relief for the people of the Donbas, and, most importantly, political will. Moscow has signaled its readiness for such a process.

For more information on Ukraine’s historical, regional, and linguistic dynamics, see my earlier entries: What Is Ukraine? (2 March 2014, updated 15 May 2014), Who Are the Rusyns? (19 April 2014), The Historical Geography of Ukraine (15 May 2014, updated 24 August 2014), and 10 Points on the People of Southeastern Ukraine (21 June 2014).