In the midst of the ongoing Ukraine crisis, one region of the country has been obscured from the spotlight. This is the westernmost Zakarpattia oblast, a mountainous region that shares four international boundaries with Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania. Located at the center of Europe, its capital is Uzhgorod, a city located literally on the border with Slovakia and which, architecturally, shares much in common with neighboring locales across the border such as Prešov and Košice. The majority of the local population is comprised of a group known as the Rusyns, a distinct East Slavic people. Most significantly, it is through this region that major energy pipelines pass from Russia, through Ukraine, and into the EU.

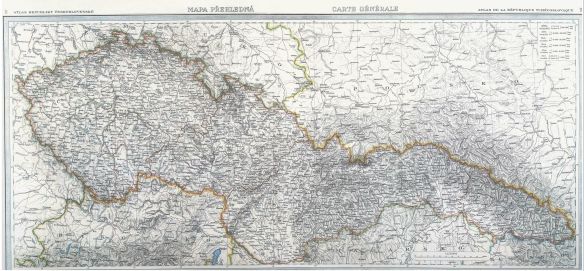

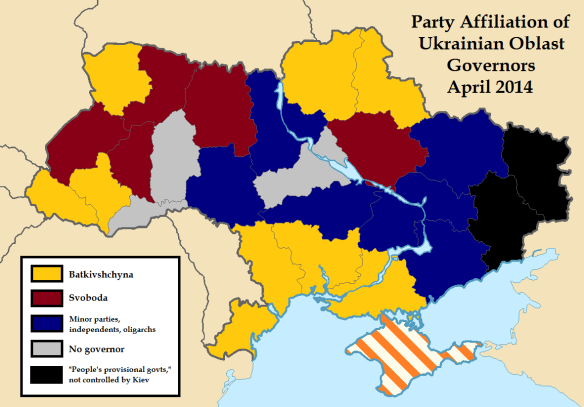

Location of the Zakarpattia Oblast within Ukraine.

Church of Archangel Michael in the wooden style commonly seen in Zakarpattia. (Sobory.ru)

Language, faith, and identity

The Rusyns derive their name from their self-designation “Rusyni” indicating “people of the Rus’ as in the old “Kievan Rus’.” At one point, the Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians all self-identified as “Rusyni” until they adopted their respective ethnonyms over time. In some cases, the residual use of the self-designation “Rusyni” in both Ukraine and Belarus lasted well into the early 20th century. The Rusyns are also known by other names too such as “Ruthenians,” a term which is also used to apply generally to all East Slavs (Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians). Indeed, “Ruthenia” is merely a Latin rendering of the name “Rus’,” though today it almost exclusively applies to Zakarpattia as a distinct region. More specific names for the people of this region include “Carpatho-Rusyns” or “Carpathian Ruthenians,” both of which designate the specific area in which these people live – the Carpathian Mountains. There are subgroups of Rusyns as well such as the Lemkos, Hutsuls, and Boykos.

Orthodox Cathedral of Christ the Savior, Uzhgorod (Ukraine Trek)

In terms of faith, the Rusyns are largely members of the Byzantine Ruthenian Catholic Church (distinct from the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church). In recent years, some Rusyns have also been gravitating toward Orthodox Christianity of the Moscow Patriarchate. In 2000, the Orthodox Cathedral of Christ the Savior was inaugurated in Uzhgorod. The church reflects common architectural styles found in much of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Yet the more prominent architectural style that one finds throughout Zakarpattia is the simple, wooden church style. Indeed, wood churches are a major art in this region and comprise an important part of the Rusyn culture, heritage, and identity.

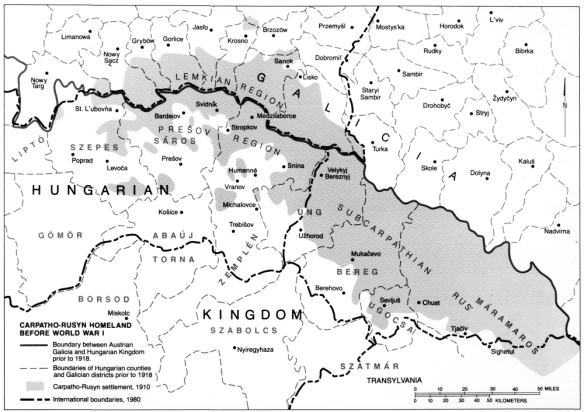

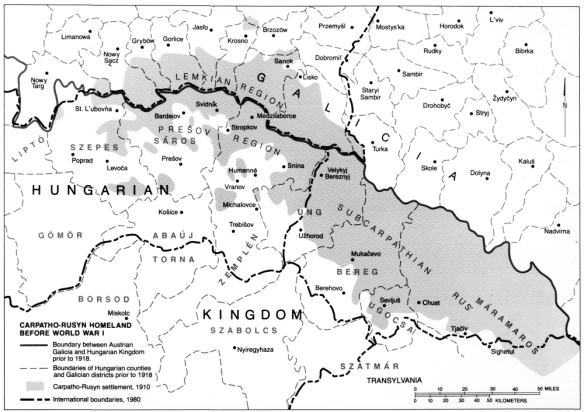

The Rusyn homeland is primarily centered on the Zakarpattia Oblast of Ukraine, which encompasses the bulk of it. However, Rusyns also inhabit a few adjoining areas, notably portions of eastern Slovakia and southeastern border areas of Poland (particularly in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship). Geography is key here for it was the mountains that isolated the Rusyns from the other East Slavs and allowed them to develop their own unique culture and East Slavic language.

Map showing the full geographic extent of the Rusyn people in Central Europe, prior to World War I. (carpathorusynsociety.org)

In fact, it is interesting to observe precisely where the Rusyn language stands within the geographic and linguistic position of the Slavic languages. In the Czech Republic, one finds the West Slavic Czech language. When one reaches the eastern fringes of the historical Czech region of Moravia, the Moravian dialect gradually begins to transition into Slovak, a language that shares many affinities with Czech. The further east one travels in Slovakia, the more divergent the Slovak dialects become from the standard language. By the time one reaches the mountainous regions of Prešov and Košice, the eastern dialects of Slovak gradually begin to blend into an East Slavic language: Rusyn.

Rusyn is the linguistically dominant language of Ukraine’s Zakarpattia oblast. From Zakarpattia, Rusyn gradually transitions into standard Ukrainian in Galicia and Volhynia. However, by the time one reaches the Khmelnytskyi oblast, Ukrainian begins to change into Surzhyk, a mixed Russian-Ukrainian language. Then, as one moves further east to the Sumy and Kharkov oblasti, Surzhyk begins to blend into Russian, specifically the southern dialect of Russian. By the time one reaches Moscow, the language has evolved into standard Russian.

The Rusyn Elite Society in Cleveland, Ohio in 1929, one of many Rusyn immigrant associations in the United States. (Cleveland Cultural Gardens)

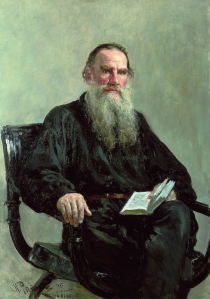

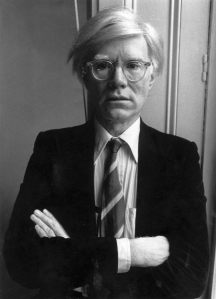

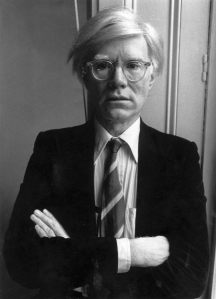

Andy Warhol

In the 19th century, significant numbers of Rusyns also moved further south from their historic homeland into the region of Pannonia. Their descendents are today the Rusyn minority in the former Yugoslavia, primarily Vojvodina, the autonomous region of northern Serbia where Rusyn is a co-official language, and in Slavonia and other regions of Croatia. Still more Rusyns emigrated to the United States and Canada in the 19th and early 20th centuries, settling in New York, New Jersey, Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, and Minneapolis, as well as parts of southern Connecticut and the coalmining towns of western Pennsylvania. One of the most prominent Rusyn-Americans who is always mentioned in discussions on Rusyns is the eccentric pop artist Andy Warhol.

Historical overview

The origins of the Rusyns can be partially traced to the White Croats, an early Slavic tribe distantly related to the modern Croats of the former Yugoslavia. The historical Rusyn homeland in Zakarpattia existed as a disputed borderland area between the Kievan Rus’ and the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. Hungary’s administration of the region strengthened following the downfall of the Rus’ state.

For many subsequent centuries, Zakarpattia remained under Hungarian rule. Thus, within Austria-Hungary, the people here were ruled by the Hungarian monarchy, in contrast to their neighbors in Galicia who were ruled directly by the Austrians in Vienna. Under Hungarian influence, the locals adopted some Hungarian cultural attributes. For example, Hungarian Bogrács Gulyás is a staple of Rusyn cuisine. The Rusyns also adopted the Catholicism of their Hungarian and Slovak neighbors. In 1646, at the Union of Uzhgorod, the largely Orthodox Rusyns formally joined the Catholic Church under the Byzantine rite, forming the Byzantine Ruthenian Catholic Church.

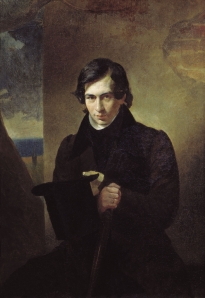

St. Petersburg-born Rusyn-Russian playwright Nestor Kukolnik (portrait by Karl Bryullov, 1836)

However, the Rusyns were far less receptive to being forcibly assimilated by the Hungarians. In the 18th and 19th centuries, a significant Russophile movement emerged in Zakarpattia in response to Hungarian cultural suppression and Magyarization. The great Rusyn writer and theologian Aleksandr Dukhnovich was active in this movement. Another was the academic Vasily Kukolnik whose St. Petersburg-born son, Nestor Kukolnik, would later become a prominent romantic Russian playwright. Russophile sentiment also existed in Galicia, though it was later supplemented by Ukrainian nationalism. By contrast, in Zakarpattia, the Russophile movement persisted even to the present-day. Indeed, many in the region still harbor affinities for Russia as evidenced by the closeness of elections here between pro-Russian and pro-Western candidates.

With the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy at the end of World War I, the West Ukrainian People’s Republic sought to claim Zakarpattia as part of its territory. However, it remained under Hungarian rule until 1919 when the Paris Peace Conference assigned it to Czechoslovakia. This was the result of a National Council led by Rusyn-American leader Grigory Žatkovich. Given the instability of Russia and Ukraine at the time, Žatkovich was advised by the Wilson administration that a Rusyn union with Czechoslovakia would be the only viable option for the territory’s future. Consequently, in 1918 Žatkovich signed the Philadelphia Agreement with Tomáš Masaryk, ensuring Rusyn autonomy in a future Czechoslovak state. The Treaty of St. Germain in 1919 reaffirmed this. However, actual political autonomy of the region proved to be less than that desired by the Rusyns of Zakarpattia, largely due to the inefficiency and bureaucracy in Prague. Žatkovich, who Masaryk appointed as governor to the region, eventually resigned in frustration.

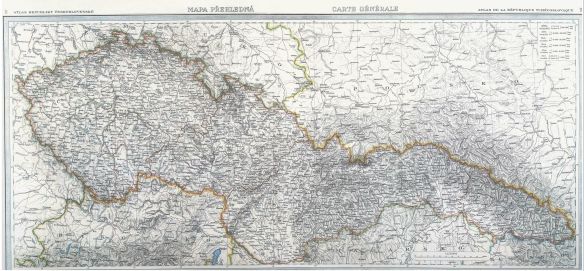

Map of interwar Czechoslovakia in 1935 with “Podkarpatská Rus” (“Subcarpathian Rus”), the present-day Zakarpattia Oblast.

Another significant aspect of Zakarpattia’s union with Czechslovakia was the precise determination of the borders. The frontiers of Zakarpattia, as determined at the Paris Peace Conference and later at the Treaty of Trianon also included a substantial Hungarian minority in the southernmost portion of the region. Most of these Hungarians did not want to separate from Hungary nor were they interested in joining the new Czechoslovak state.

Following Hitler’s annexation of the German-inhabited Sudetenland in 1938, the remainder of Czechoslovakia was slowly dismembered. Germany moved to snatch the rest of the Czech lands while Slovakia became a German fascist puppet state ruled by the collaborator Jozef Tiso. Horthy’s Hungary then was given permission by Hitler to annex the Hungarian-inhabited areas of southern Slovakia in the First Vienna Award. The Nazis also granted Zakarpattia to Budapest as well. This left the region with no choice but to declare its independence. On March 15, 1939, the Rusyns moved to declare a Republic of Carpatho-Ukraine. Within one day, it was crushed by Horthy’s invading army and declared part of Hungary. Under Hungarian rule, the Rusyns were allowed to continue reading and writing in their language as long as it was pro-Hungarian in orientation. Those opposed to Hungarian rule sought to flee Zakarpattia across the mountains into Soviet Ukraine. Hoping to be welcomed by the Soviets, they were instead arrested by the NKVD for “illegally crossing into Soviet territory” and sent to Gulag labor camps. Meanwhile, during the war, Zakarpattia’s historic Jewish community suffered greatly. Most were deported to Nazi death camps and perished in the Holocaust.

A Soviet-era stamp celebrating the 20th anniversary of Zakarpattia’s “reunification” with Soviet Ukraine.

Zakarpattia remained part of Hungary for much of the war until it was liberated by Soviet troops in 1944. Throughout the war, Moscow promised the Western allies that it would restore Czechoslovakia’s pre-1938 borders. However, after the liberation of Zakarpattia, new considerations were drawn up and it was decided to incorporate the region into Soviet Ukraine instead. The decision was informed by both ethnic-historical and geopolitical considerations. With the Soviet incorporation of the region, all of the historic East Slav lands were now under the jurisdiction of a single state for the first time since the Kievan Rus’. Geopolitically, the region was also strategically significant, as it gave the Soviet Union a direct land boundary with Hungary. The cession was officially acknowledged by Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš in June 1945. The borders of Zakarpattia remained virtually unchanged except for the new addition of the border city of Chop, an important railway juncture.

The incorporation of Zakarpattia into the Soviet Union brought about significant changes. The Soviets attempted to modernize the economy and to bring collectivization to the countryside. The Soviets also attempted to suppress the native Byzantine Ruthenian Catholic Church. Though instead of moving to repress religion, they sought to bring this church under the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church. This was met with limited success, though Orthodoxy in Zakarpattia has arguably experienced some activity since Ukraine’s independence.

The Soviets also inherited Zakarpattia’s community of Jehovah’s Witnesses, the result of missionary work in interwar Czechoslovakia. The Soviets distrusted the Witnesses as a “non-traditional sect” and thus sought to limit their activities. Yet, the Witnesses continued to pursue their beliefs regardless and earned a degree of respect in Soviet society for their “dissident” and “anti-Soviet” approach.

A still from Parajanov’s Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.

Meanwhile, education and literacy were also promoted as was Russian-language instruction. Ethnic Russian teachers, workers, and supervisors from Moscow descended on the new region, creating a new Russian minority. They also were genuinely astounded by this unique and mountainous “lost province” that, in their view had been separated for so long from the “Russian motherland.” The fascination with Zakarpattia continued for much of the Soviet era and was even the subject of films and popular media. The great Soviet Armenian filmmaker Sergei Parajanov even made a film about Zakarpattia called Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors that met with critical acclaim internationally.

The Soviet nationalities’ policy also sought to promote the “Ukrainian” ethnonym among the Rusyn people of this region. The ethnonym has been largely adopted by the people, though most still speak the Rusyn language and adhere to their own cultural norms. The sense of uniqueness also persisted, though any debate about the Rusyn question was banned in the Soviet Union until glasnost. Under Gorbachev, discussion of the “Rusyn question” began to re-emerge and the Byzantine Ruthenian Catholic Church was rehabilitated. In 1991, voters in Zakarpattia overwhelmingly backed Gorbachev’s New Union Treaty. Later that year, Ukraine’s Kravchuk proposed a ballot on state sovereignty in Ukraine. This too was approved by voters in the region. However, more significantly, another provision on the ballot promising local autonomy passed by an even wider margin. Despite this vote, autonomy for the region was never granted.

Fr. Dmitro Sydor

In 2008, some activists unsuccessfully attempted to declare a “Republic of Carpathian Ruthenia.” Those involved were later sent in for questioning by the Security Service of Ukraine for challenging “state integrity.” They included Fr. Dmitro Sydor, a Mukachevo-born priest of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) and chairman of the Congress of Carpathian Ruthenians. The main goal of the Congress is to achieve autonomy for the region. In March 2012, Sydor was found guilty for violation of the territorial integrity of Ukraine. He was sentenced to three years imprisonment with a suspended sentence of two years.

Politically, the region’s leanings have been mixed. As referenced earlier, Zakarpattia’s electoral politics is more like that of a Central Ukrainian than a Western Ukrainian region. The Party of Regions managed to carry Zakarpattia in the 2012 Ukrainian parliamentary election, contesting it heavily with Tymoshenko’s Batkivshchyna Party and the centrist United Center Party which draws its main base of voters from this region. In the 2010 presidential election, Tymoshenko won Zakarpattia, but by a very narrow margin against Yanukovych.

Meanwhile, the substantial Hungarian minority of Zakarpattia remains at a crossroads. Successive Hungarian governments have made a point to defend Magyar minority rights in neighboring countries. The Hungarians of Zakarpattia were no exception, and to this end, Hungary’s Viktor Orban supported of former Ukrainian President Yanukovych who placed great emphasis on protecting linguistic rights.

Since the Euromaidan revolution, the local Hungarian community has been uneasy and has viewed the influence of the far-right in the government as a serious concern. Among other things, local Hungarians were concerned about the initiative by the government (since abandoned) to scrap Ukraine’s regional language law. Fortunately, in the wake of the unrest in Eastern Ukraine, the Turchynov-Yatsenyuk government has announced that it will allow for enhanced linguistic rights in the various oblasti. Also, the Orban government in Budapest has opened the door in recent years for Hungarians abroad to receive Hungarian passports. This has been very significant for Hungarians in Zakarpattia, wary of nationalism in Ukraine and eager for jobs in the EU.

It is still unclear what full impact the Maidan revolution will have on the Rusyns. The region is currently governed by a member of the Batkivshchyna party appointed by the Turchynov-Yatsenyuk government. However, there is uncertainty with regard to how influential Kiev is in this region and how much support it has. It is very likely that most of the people here would favor a new federal constitution for Ukraine which would finally give them their long-desired autonomy. Yet, as always, what happens next remains to be seen.

UPDATE (13 June 2014): Watch rare footage of life in Zakarpattia/Carpathian Rus’ in interwar Czechoslovakia from the Czech National Film Archive here!