The ongoing situation in Ukraine is a crisis that has drawn in the United States, the EU (represented by Germany and other West European powers), and Russia. However, also significant are the minor parties to this dispute. These are Poland, Sweden, and the three Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. Collectively, they together form a “Baltic Bloc” of the EU that is especially apprehensive about and hawkish toward Russia. The reasons for this vary among these countries, but most are rooted in security concerns and historical animosities. In the cases of Poland and the Baltics especially, NATO membership combined with support from Washington has only encouraged them in their anti-Russia posturing. The concern with Russia has been particularly pronounced in the former Soviet Baltic republics where memories of the forced Soviet annexation by Stalin remain widespread. This past week, it was announced that the US had deployed fighter jets to Baltic states and Poland in light of the Ukraine crisis.

Map of the EU’s Baltic Bloc of Poland, Sweden, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia in light beige with Ukraine in blue.

Why is the Baltic Bloc significant to the ongoing Ukraine crisis? Part of the reason goes back to the very institution that sponsored the potential integration of Ukraine in the EU. This was the Eastern Partnership (EaP), proposed on May 22, 2008 as a joint initiative by the two largest Baltic Bloc states, Poland and Sweden. The EaP’s founding was inauspicious and did not receive much attention until it was officially launched a year later on May 8, 2009. Its primary aim was (and still is) the integration of the countries of the former Soviet west – Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine – into the European Union.

Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski (left) and Swedish Foreign Minister Carl Bildt (right). (AP)

“It’s time to look to the east to see what we can do to strengthen democracy,” said Swedish Foreign Minister Carl Bildt on the founding of the EaP. Adding to this, Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski stated, “we all know the EU has enlargement fatigue. We have to use this time to prepare as much as possible so that when the fatigue passes, [EU] membership becomes something natural.”

The main initiator of the EaP was Poland. Warsaw wants to strengthen its regional position and also to counterbalance both Germany’s power within the EU and Russia’s perceived geopolitical assertiveness. In order to give the EaP initiative gravitas, Poland also sought support from Sweden. Concerned about their security vis-a-vis Moscow, Stockholm welcomed co-sponsorship. However, in order to fully understand the motives of these two states more deeply, a brief overview of their historical relationships with Russia must be in order.

Why Poland?

Poland specifically has a long and complicated history with Russia. In sum, its acceptance of Roman Catholicism and its orientation toward Western Europe and the Latin world distinguished it against Orthodox Russia with its Byzantine identity and mixed European-Asian outlook. In the West, we often look to the most recent history of the Russian-Polish conflict where Poland is the victim of Russian and Soviet imperialism. Mentioned are events like Russia’s participation in Poland’s partitions, its suppression of Polish uprisings, the Polish-Soviet War, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Katyń massacre, and the establishment of communist Poland after World War II.

![The Oath of False Dimitry I to Sigismund III [King of Poland-Lithuania] on the Introduction of Catholicism in Russia by Nikolai Nevrev.](https://reconsideringrussia.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/false-dimitry.jpg?w=236&h=300)

The Oath of False Dimitry I to Sigismund III [King of Poland-Lithuania] on the Introduction of Catholicism in Russia (1874) by Nikolai Nevrev.

More importantly, the Time of Troubles also includes the 1609 invasion of Muscovy by the Polish monarch Sigismund III, who hoped to forcibly annex Russia and proclaim himself ruler of a joint Polish-Russian state. The occupation of Moscow by the Poles and their unsuccessful attempts to forcibly convert Russia to Roman Catholicism during this period are especially sensitive subjects for the Russians to this day.

In firm opposition to the Polish invasion was the Russian Orthodox Patriarch Hermogen, who was imprisoned by the Poles for refusing to endorse a non-Orthodox tsar. From his cell, he called upon the mass of the Russian narod to rise up and expel the invaders from the motherland. Additionally arousing Russian national feeling was Sweden’s decision in the autumn of 1610 to join the Poles in their fight against Russia.

The Polish occupation of Muscovy was ultimately overturned in 1612 by a successful national rebellion, led by an unlikely duo comprised of a local butcher Kuzma Minin and a veteran military leader Prince Dmitriy Pozharsky. Subsequently, these leaders called the national assembly that led to the election of Mikhail Romanov to the Russian throne, thus initiating the Romanov dynasty. The national significance of Minin and Pozharsky’s leadership would later become immortalized in a monument dedicated to them that stands today on Red Square in front of St. Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow. Notably, the monument was completed in 1818, immediately following the victory against the Napoleonic invasion of 1812 and approximately 200 years after the victory against the Poles. In general, these historical memories, though seemingly distant to Westerners, still influence many Russians today and continue to inform their views on geopolitics with regard to Europe. It is a history that every Russian school child knows.

In much more recent times, following the collapse of communism, the Russo-Polish relationship entered an overtly antagonistic phase under the presidency of Lech Kaczyński (2005-2010). A textbook Polish nationalist, Kaczyński held a genuine distrust for both Germany and Russia. Within the EU, he generally earned a reputation for being hawkish on Russia and staunchly loyal to Washington. He was an active supporter of the war in Iraq as well as efforts to support the “color revolution” governments in Ukraine and Georgia and to expand NATO eastward. As one commentator from Der Speigel noted:

Since it expanded into Central Europe and parts of the former Soviet Union in 2004, Poland and the Baltic states have pushed the EU to take a stronger stance against Russia — to the dismay of many diplomats in what some call “Old Europe.”

During the 2008 Georgian war, Kaczyński reacted by flying to the Georgian capital of Tbilisi with the pro-Western Ukrainian President Viktor Yuschenko and the presidents of the three Baltic states. Together, they “stood in solidarity” with Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili. In a speech, he proclaimed, “you could say that the nation of Russia yet again showed its true face here today. The aggression here is nothing new when it comes to history.” Kaczyński shared close relations with Saakashvili. Significantly, after Kaczyński’s death in April 2010, Saakashvili called him a “hero of Georgia” and implied foul play in the tragedy (presumably by Russia, though there has been no evidence of this). Later, the Georgian president unveiled a monument in Kaczyński’s honor in Tbilisi.

Lech Kaczyński stands with Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili, Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko, and the presidents of the three Baltic states in Tbilisi during the 2008 South Ossetia war. (AFP)

Kaczyński also enthusiastically welcomed the Washington-proposed missile defense shield in Poland which Moscow considered a threat. Likewise, he envied and feared Germany’s wealth and power within the EU. Following Kaczyński’s death, his twin brother Jarosław (who shared much of his brothers’ political views) warned Berlin against “imperial ambitions” and authored a book in Poland that suggested German territorial ambitions on Poland, and that the East German stasi helped Angela Merkel win power. Between both Germany and Russia, the Kaczyńskis saw Poland again as being a “victim in the middle,” a fact seemingly emphasized by then-Defense Minister (today Foreign Minister) Radosław Sikorski’s comparison of the joint German-Russian Nord Stream pipeline to the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. Clearly the historical memory of Poland’s partitions and divisions still runs deep in the Polish consciousness.

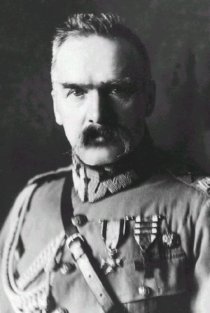

It should likewise be noted that Kaczyński also deeply admired Józef Piłsudski, a Polish military leader and dictator from Poland’s interwar past, and his ideology of “prometheism” which likely influenced his perspective as well. The “prometheist” policy of Piłsudski viewed large areas of Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania as crucial to forming a larger, multiethnic Poland as had existed immediately prior to its first partition in 1772. Additionally, there are also many Poles who continue to view the “Kresy” (“Borderland”) territories of Western Ukraine, Western Belarus, and Southern Lithuania as still being rightfully theirs. Consequently, it is in Ukraine where Poland’s historical-national ambitions coincide with its security concerns. Notably, Kaczyński’s ally, Mikheil Saakashvili, is also an admirer of Piłsudski.

Yet, for all this, the overtly antagonist atmosphere of Russian-Polish relations under Kaczyński did not last long. In 2010 Kaczyński died in a tragic plane crash near Smolensk. Early presidential elections were called. Kaczyński’s twin brother Jarosław ran in his place and lost against the independent Bronisław Komorowski. It must be noted that Komorowski hails from Poland’s “recovered territories,” the formerly German-inhabited regions of western Poland annexed after World War II, where the attitude toward relations with Russia is more pragmatic. Likewise, Prime Minister Donald Tusk, elected to office in 2007, is also from the “recovered territories” and has supported better relations with Moscow.

Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski (http://www.radeksikorski.pl/)

Under Komorowski and Tusk, relations between Poland and Russia have improved. However, it was also under the Tusk government with the encouragement of Defense Minister-turned-Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski that the EaP was founded, thus indicating a continued interest in enhancing Poland’s role in the ex-Soviet space. In fact, Sikorski had proposed the idea for the EaP as early as March 2008. It is conceivable too that while the Tusk government has sought to maintain a balanced relationship with Moscow, it also still seeks to counterbalance Germany’s influence within the EU and Russia’s influence in the post-Soviet space. Overall, tension with Moscow still remains. Historical animosities continue to be highly flammable, as demonstrated by the violent clashes between Russian and Polish football fans during the FIFA Euro 2012 Poland-Russia football match in Warsaw. According to a 2013 Pew Research poll, 54% of Poles expressed an unfavorable opinion about Russia.

Why Sweden?

A 2009 Polish report on the EaP indicated that the concept “was born in Poland” and that Sweden later decided to co-sponsor the initiative. Indeed, the report states, “thanks to Sweden’s involvement, the development of an independent EU Eastern policy ceased to be perceived as a sphere of interest of primarily the ‘new’ [i.e., ex-communist] EU member states.” Though the same report identifies “the principal motivation behind Sweden’s involvement” as being its “support for bringing those countries closer to the EU,” it does not state any reasons for this. The historic Swedish-Russian relationship offers some insight into this issue. Stockholm’s relationship with Russia has been dominated since the 19th century primarily by security concerns which have their origins in earlier military conflicts.

Russian national hero Aleksandr Nevsky as depicted in the 1938 Eisenstein film of the same name. Hear the film score by Prokofiev here.

Much like the Polish-Russian relationship, the historic relationship between Russia and Sweden also has deep roots. Some historians even argue that the Rus’ people have at least partial Scandinavian origins. This aside, Russian-Swedish relations have largely been characterized by mutual mistrust and hostility. The two countries fought 15 wars against one another, beginning with the Swedish–Novgorodian wars of the 12th and 13th centuries, including the famed Battle of the Neva in 1240 in which the Prince Aleksandr of Novgorod earned the epithet “Nevsky.” However, it was the Great Northern War that marked a major turning point in the relationship between both countries. It was during that war that Tsar Peter the Great captured a strategically important stretch of territory on the Gulf of Finland where he founded for Russia a new, European-oriented capital, St. Petersburg. It was also during the war that the Battle of Poltava was fought. On June 27, 1709, on the Poltava field of eastern Ukraine, Peter decisively defeated the Swedish forces of King Charles XII and his Field Marshal Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld. The defeat marked the beginning of the end of Sweden as a Great Power in Europe.

The last war fought between Russia and Sweden was a century later in 1808-09 in which Russia annexed Finland. Then, despite a lengthy history of tension, the two Baltic rivals set aside their mutual animosity to combat a much greater common foe, Napoleon in 1812. After his defeat, however, the frosty relationship between St. Petersburg and Stockholm resumed. Sweden bristled at Russia’s continued fortifications of the majority-Swedish Åland Islands, located only 135 miles from Stockholm. Following its territorial losses to Russia in the Great Northern War and its additional loss of Finland in 1809, many Swedes continued to fear the possibility of a Russian attack from across the Baltic Sea. For its part, Russia too feared a possible attack by its northern neighbor.

In the 20th century, though officially neutral in World War I and World War II, Stockholm nonetheless supported Finland in its quest for independence from Russia and later in its Winter War with the Soviet Union. In both instances, popular opinion remained distrustful of Russia and support for the Finns ran high. Sweden maintained a policy of neutrality during the Cold War, but it was a policy that Moscow did not fully trust. It included incidents such as the 1952 Catalina affair in which Soviet fighter jets shot down a Swedish reconnaissance aircraft (DC-3) and a search-and-rescue plane. Moscow officially denied any involvement until the Soviet collapse in 1991. In another incident, the Soviet Whiskey-class submarine S-363 ran aground in Sweden’s Karlskrona archipelago from its Baltic Fleet base in Soviet Latvia in October 1981.

Espionage was another aspect of the Cold War relationship. Sweden rendered support to Britain’s Mi6 to train intelligence and resistance agents of Polish and Baltic descent for “Operation Jungle.” The operation was intended to help reinforce anti-communist resistance in the Moscow-backed People’s Republic of Poland and in the then-Soviet Baltic states in the 1940s and 1950s. For its part, Stockholm arrested three Soviet spies: Fritiof Enbom in 1952, Stig Wennerström (a colonel in the Swedish Air Force) in 1963 and Stig Bergling in 1979.

With the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Sweden’s traditional security concerns with Moscow changed entirely. Suddenly, the long Soviet-Swedish maritime border in the Baltic Sea ceased to exist and was now replaced by maritime borders with the Russian Federation and the three Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Sweden viewed the three new Baltic states as an important “buffer” against any future Russian threat and thus were viewed as crucial to Stockholm’s security (and to some extent, the security of Scandinavia in general). The sentiment was reciprocated in the Baltics, whose memories of their forced incorporation into the USSR ran deep. The Scandinavian orientation is especially pronounced in Estonia where there have even been proposals to revise their national flag to include the Nordic cross. In 2011, Sweden formally apologized to the Baltic states “for turning a blind eye to post-war Soviet occupation.”

Overall, the relationship between Stockholm and Moscow in the 1990s was generally good. The perception of Yeltsin’s Russia being a weak state at once significantly reduced traditional security concerns and created new ones (e.g., a mass migration of Russian workers or concerns regarding the security of nuclear weapons). This all changed with the Putin presidency, in which the “new” concerns of the 1990s were supplemented again by traditional security concerns. In contrast to the wild Yeltsin years of free-fall capitalism, Putin’s tenure stressed a greater sense of stability. From the outset, the new Russian president sought to reverse the worst excesses of the Yeltsin era. For Sweden, this meant that the stability concerns stemming from the Yeltsin 1990s would be addressed. However, it also meant the re-emergence of a strong, viable state in Russia that could again potentially present a military threat to Stockholm. Consequently, while a member of the Swedish government may state publicly that their opposition to Russia is based on “conflicts in values,” the reality is that it has more to do with perceived Russian state consolidation and its potential implications for Swedish security.

Beginning in the 2000s, a noticeable chill had descended on relations between the two states once again. Alongside Lech Kaczyński’s Poland, Sweden soon became one of the most hawkish voices on Russia in the EU. It was a very vocal in its condemnation of the Second Chechen war and provided a safe haven to former separatist leaders, irritating Moscow. Notably, a Swedish web server still hosts a website known as the Kavkaz Center, the online voice for the militant Islamic Caucasus Emirate, designated as a terrorist organization by Russia and the United States. Moscow has periodically urged Stockholm to ban the site, which as of March 2014, it has not yet done. Stockholm has also given unequivocal support for the expansion of NATO and for the new “color revolution” governments. In light of the 2008 Russian-Georgian war, Foreign Minister Carl Bildt compared the actions of President Putin with those of Adolf Hitler. Military ties were immediately severed.

In 2005, Stockholm opposed the Nord Stream pipeline between Russia and Germany. Among its concerns were a fear of “increased energy dependence on Russia,” “increased Russian military activity in the Baltic Sea (since the pipeline must be guarded),” and “use of the gas installations by Russia to spy on Sweden.” However, in 2009, Sweden reversed its position and decided to give the green light on Nord Stream.

Regardless, the situation remains tense. By 2011, in response to Russia’s increase military buildup, Education Minister and Deputy Prime Minister Jan Björklund proposed the installation of military units on the Baltic island of Gotland in case of war between Russia and Sweden. Then, on Good Friday 2013, Russia conducted a military exercise in the Baltic Sea, simulating an attack on Stockholm. Though Moscow insisted that it had informed Stockholm of such an exercise, Sweden was caught totally by surprise. It is likely that the Russian exercise was done in response to earlier NATO exercises held in its vicinity, notably in Norway in March 2012, and to the planned NATO “Steadfast Jazz” exercise in Poland and the Baltic states that was later held in November 2013. The incident fueled a growing debate in Sweden about finally abandoning the country’s historic neutrality and joining the NATO military alliance. The inadequacies of the Swedish military were later satirized on a comedy program on Russian television to the tune of ABBA’s Mamma Mia. The Swedes were not laughing. A 2013 survey revealed that 76% have a negative opinion of Russia.