Updated on 15 March 2015 with newly revealed information on Crimea.

Ukraine’s Petro Poroshenko and Russia’s Vladimir Putin are in a pickle. Both presidents have a crisis on their hands in Ukraine. Both presidents know genuinely how to resolve it: through diplomacy and dialogue. However, the currents of the crisis in Ukraine, and that of history in general, seem to be moving faster than either gentlemen would prefer.

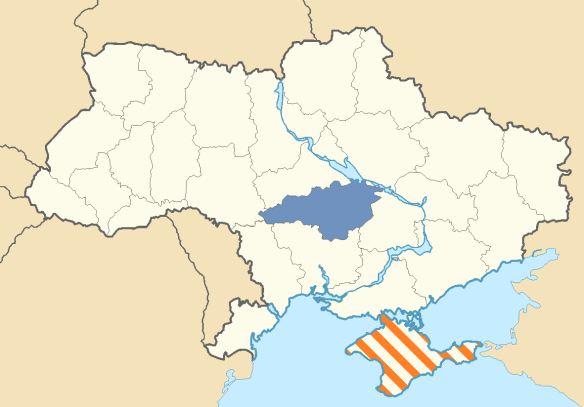

Following his election as Ukraine’s President, the Podolian “Shokoladni Tsar” Poroshenko inherited the so-called “anti-Terrorist operation” from the Yatsenyuk government. Poroshenko seems to want to end the conflict and has vocally sought to reach out to his Russian-speaking compatriots in the Donbas. Yet at the same time, he appears restrained in what he can do, and at times even appears to even endorse the controversial “anti-Terror” campaign that has thus far cost hundreds of lives, including many civilians. There are at least three reasons for this.

One is that the 2004 Orange Revolution constitution was restored in Ukraine, which effectively means that the Ukrainian parliament, the Rada, has more power than Poroshenko. Therefore, by law, Poroshenko is limited in what he can do.

Dmytro Yarosh, leader of the far-right paramilitary organization Right Sector, flanked by two members of the group. Right Sector has actively participated in the controversial “anti-terrorist operation” in the Donbas in which hundreds of civilians have died. (Reuters / David Mdzinarishvili)

The second problem that Poroshenko faces is the fact that the “anti-Terrorist operation” is led by a disparate assortment of groups including Right Sector (Praviy Sektor) and other far-right militants, the Maidan self-defense forces, oligarch-financed militias (effectively “private armies”), and (allegedly) mercenaries from other countries. The regular Ukrainian army, with defections and desertions, has proved to be unreliable for Kiev. Therefore, to “reign in” the rebels, it relies on these “independent” groups and militias. The problem with this strategy is that the latter are truly “independent” and thus it is difficult for Poroshenko to command them to “stop,” even though he is now calling for a cease-fire.

Finally, Poroshenko is under pressure from rival political forces, primarily the Batkivshchyna party and its leader Yulia Tymoshenko, who has threatened to launch “another Maidan” if Poroshenko’s presidency proves to be a disappointment. In a concerning development, the usually pro-Western and liberal Batkivshchyna now appears to be co-opting itself with Ukraine’s nationalists. In fact, since this crisis commenced, nationalism and Russophobia appear to have become increasingly prevalent within the Ukrainian political elite; though it is doubtful that these attitudes reflect the popular sentiment of the vast majority of Ukrainian people.

On the Russian side, Putin is in a no less enviable position. Despite Western and Ukrainian allegations that the Donbas rebels are effectively Russian puppets, the truth is that they are indeed largely comprised of locals. However, they do indeed have supporters and handlers across the border in Russia. These are primarily extremist and nationalist Russian political forces led by fanatical ideologues and writers like Aleksandr Dugin and Aleksandr Prokhanov and fierce commanders like Igor Strelkov. They write for far-right Russians gazetas like “Zavtra,” reenact battles from the 1918-22 Russian Civil War as White Army officers, and like their nationalist Ukrainian counterparts, they too harbor antisemitic sentiments. They dream of forging an authoritarian Eurasian state, a vision that (despite Western rhetoric) is in fact quite different from post-Soviet integration schemes like Putin’s Eurasian Union or similar ideas proposed by Mikhail Gorbachev, Kazakhstan’s Nursultan Nazarbayev, and others in the past.

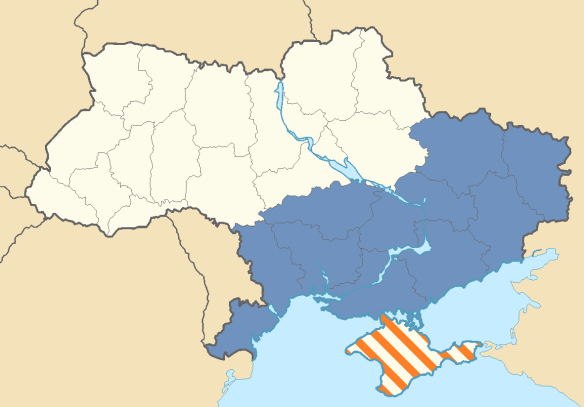

The Russian nationalists supporting the Donbas rebels are not officially backed by the Russian government. Instead, they are acting out of sheer nationalist zeal. However, hardliners among Russia’s political elite, like Dmitry Rogozin, are putting great pressure on Putin to intervene to support the rebels. For his part, Putin has to balance relations between the hardliners like Rogozin and the more liberal wing of the Kremlin represented by Dmitry Medvedev and other liberals from Putin’s Sobchak days. As I wrote earlier, the hardliners earlier demanded that Putin immediately annex Crimea. The Medvedev group supported a referendum on the issue but ultimately favored caution, arguing that an outright annexation would make relations with the West worse. In the end, Putin ordered a special operation in Crimea in which the troops of the Black Sea Fleet gained control of the peninsula as a so-called “self-defense force.” He also took the position that he would support the final outcome of the Crimean referendum, whatever the result. In the end, the population voted for the incorporation of Crimea into Russia and Putin backed this decision.

This has not occurred with the Donbas and Eastern Ukraine. Despite invoking the rhetoric of “Novorossiya,” Putin has refrained from intervening in Ukraine, a decision that was likely not only influenced by Medvedev and the liberals, but also by other dynamics as well. These include the mere fact that the division between the Russian-speaking oblasti and the mixed Russo-Ukrainian Surzhyk-speaking oblasti in Ukraine is ambiguous. Thus it would be very dangerous for Russia to intervene militarily, if only for this reason. Further, Putin had clear geopolitical objectives in Crimea centered around concerns regarding the Black Sea naval base and potential NATO expansion. There are no such geopolitical concerns for Eastern Ukraine specifically, though in the bigger picture, the fate of Ukraine as a totality is important for Russia geopolitically. That said, while Russia will likely not intervene militarily in Ukraine to support the Donbas rebels, it may lend itself to other initiatives, including establishing a humanitarian corridor. Given the outcry in the Russian public over the atrocities and violence occurring in the Donbas in Kiev’s controversial “anti-terrorist operation,” this may very well happen.

Finally, it must be noted that a major shortcoming and self-defeating factor of the Donbas rebels is their narrow focus. Their ideology is based on Russian nationalism, Orthodoxy, Russian-speakers, the southeastern oblasti of Ukraine, and “Novorossiya” (even though Novorossiya historically did not cover all of the Russian-speaking oblasti). However, this hardly makes for a viable ideology that can attract large numbers of people and that the Kremlin can feel justified in supporting. Such an ideology may find traction in the Donbas where sympathies for Russia run particularly high. However, in the old Sloboda Ukraine (centered on Kharkiv), historic Zaporozhia (centered on Dnepropetrovsk), and the “core” of Novorossiya (cities like Odessa and Nikolayev), the ideology of the rebels has garnered very little traction, even if the population has a strong dislike of the post-Maidan government and disapproves of the atrocities being committed in the so-called “anti-Terrorist operation.” Also, most have no interest in seceding from the Ukrainian state, even though they strongly dislike the current government.

Further, while the majority of the locals in Southeastern Ukraine speak Russian and take their cultural cues from Russia, they still identify as ethnic Ukrainians. Tsarist-era censuses (particularly the 1897 census) attest to the fact that the people of this area largely self-identified as “Malorussians” (i.e., Ukrainians) in Tsarist times. Hence, the people of these oblasti are indeed of Ukrainian origin and are not ethnic Russians who simply adopted the “Ukrainian” ethnonym in the Soviet era. Therefore, unless the rebels think in terms of “Ukraine” as opposed to “the Donbas” or “Novorossiya,” most southeastern Ukrainians will continue to view them with skepticism.

As the Ukraine crisis enters a violent, prolonged military phase, its greatest tragedy is that the people of the Donbas and other regions of Ukraine will continue to suffer in the process, becoming cannon fodder for rival Ukrainian and Russian nationalist visions. Meanwhile, Putin and Poroshenko will continue to remain hostage to events that are unfolding fast. History will proceed, regardless of what either president has to say about it.