Updated and revised on 20 September 2016 with additional information, including the economic and political roots of the Transnistrian conflict (in addition to the historical factors). Please note that this entry was originally written in April 2014 and thus does not cover subsequent political developments in Moldova, such as the rise of the Euroskeptical and pro-Moscow Party of Socialists and Patria-Rodina bloc. It also does not cover subsequent events in Ukraine, such as Mikheil Saakashvili’s appointment to the governorship of the Odessa Oblast.

Map of Moldova, Transnistria, and Gagauzia

Moldova and its breakaway region of Transnistria have been in the news a lot lately. I will attempt to give some historical background to this complex borderland in my analysis below.

The EU’s Eastern Partnership (EaP) program included within its scope the six countries of the former Soviet west. These were Belarus, Moldova, and Ukraine in Eastern Europe and Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia in the Caucasus. Of the six, Belarus and Azerbaijan expressed little interest in the project. However, the remaining four states – Armenia, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine – actively participated in it. The motives of these states’ involvement in the EaP varies. In the cases of Armenia, Georgia, and Ukraine, the leaderships of these countries used the geopolitical competition between Russia and the West to get the best terms for their countries. Armenia’s Sargsyan and Georgia’s Ivanishvili have both played this chess game especially well as their countries have a history of playing Great Powers off of each other to their own advantage. In this respect, they are neither categorically “pro-Russian” nor “pro-Western,” but rather “pro-Armenian” and “pro-Georgian” respectively. Ukraine’s Yanukovych attempted to play this game too but proved far less decisive and pragmatic than his Caucasian counterparts. Meanwhile, the leadership of Moldova has pursued an entirely different path. It seeks to fully free itself from Moscow’s orbit and to integrate into the EU regardless.

Romanian President Traian Băsescu (left) and Moldovan President Nicolae Timofti (right) in Chișinău in July 2014 (President of Romania)

Indeed, if there is one state out of all the EaP countries that is thoroughly committed to Europe and sincerely interested in leaving Moscow’s orbit once and for all, it is Moldova. The leadership in Chișinău, under President Timofti and Prime Minister Leancă, is entirely committed to the idea of firm and total European integration. Additionally, out of all the EaP states, Moldova is arguably in the best position to become a candidate for EU accession geographically, politically, and economically, making it an “easy pill to swallow” by EU standards. Within the EaP, Moldova also represents a very unique case because their main backer within the EU is Romania. Romanian President Traian Băsescu has lobbied hard for Moldova’s integration into the bloc and would never allow his ethnic Latin Vlach cousins to end up outside of the EU. In the early 1990s, Romania was the first country to recognize Moldova’s independence. It also has allowed for Moldovan citizens to obtain Romanian passports. This has caused a large flow of Moldovans to enter the EU “through the back door.”

Historical background

Mihai Eminescu in Prague, 1869

The reasons for the close Romanian-Moldovan relationship are both ethnic and historical. Moldova corresponds almost exactly to the historical Romanian region of Bessarabia, located between the Dniester and Prut rivers. The majority of its population are ethnic Romanians, who speak Romanian. The colors on the Moldovan flag are almost exactly the same as those on the Romanian flag. Likewise, both countries consider the Romanian poet Mihai Eminescu to be their national poet. Along with a good portion of eastern Romania, Bessarabia had once formed a major portion of the old Vlach-speaking principality of Moldavia. In 1812, it was annexed by the Russian Empire, but after the 1917 Russian Revolution, the region’s local leaders formed a National Council (Sfatul Ţării) and voted to join the Kingdom of Romania in 1918. It remained a part of Greater Romania for much of the interwar period.

As a challenge to Romania’s control of Bessarabia, the Bolsheviks created the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) in 1924 in Soviet Ukraine. Most of the territory of the Moldavian ASSR corresponds to the now-breakaway region of Transnistria. Inhabited primarily by a mixed population of East Slavs and Romanians, this territory was never part of Bessarabia or the historic principality of Moldavia. The Soviets instead used the region as a means of arguing that the Moldovans were not a branch of Romanians but an entirely unique people.

“Scholars from the West, in particular the German ethnographer Gustav Weigand, had noted earlier in the century that Romanian-speakers in Bessarabia and Bukovina spoke a dialect distinct from those in the Romanian kingdom,” wrote historian Charles King in his excellent overview, The Moldovans, “but these differences were no more striking than regional variations inside Romania itself. In the MASSR, however, these distinctions were imbued with political meaning.” These dialectal differences served as the basis for the creation of a new “Moldovan” language, which, despite its Cyrillic alphabet, was virtually identical to Romanian.

Maps of Romania and Moldova. The top map from 1926 shows the interwar Kingdom of Romania including Moldova within its borders. The bottom map from 2001 shows the present-day boundaries of Romania and Moldova.

In June 1940, the USSR annexed Bessarabia as part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Most of the area was united with much of the old Moldavian ASSR (modern Transnistria) to form the new “Moldovan SSR.” When the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union during World War II, Romania under the fascist leadership of Ion Antonescu joined the German war effort. The Romanian forces not only regained Bessarabia from the Soviets but pressed on further east to take all of the territory between the Dniester and Southern Bug rivers, including the historic city of Odessa. The new territory, administered by Romania, was called “Transnistria.” Hitler granted it to Antonesu as compensation for giving Transylvania to Horthy’s Hungary in the Second Vienna Award. The Romanian administration of this “Transnistria” was very brutal for the local population, especially for the Jews. When the tide turned in the war, the region was recovered by the Soviets along with Romanian-speaking Bessarabia. By the end of the war, the 1940 borders between the Soviet Union and Romania were now reestablished.

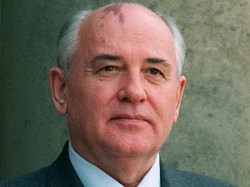

With the onset of perestroika, nationalist elites in Moldova began to gain power and sought to reunite their republic with Romania. However, political concerns prevented this from occurring. Reunification was especially rejected by the people of Transnistria who bristled at the new nationalistic rhetoric from Chișinău. In contrast to the nationalist elites gaining influence in the capital, the Transnistrians argued that they had never been part of historic Bessarabia. Many also still had memories of the brutal wartime administration of Transnistria by Antonesu’s Romania. “The Transnistrian war was in no sense about ancient hatreds between eastern Latinity and Slavdom,” wrote King, “but history did play an important role.”

No less significant to the conflict were economic, social, and political factors. Whereas most of Moldova west of the Dniester was largely rural and agricultural, Transnistria was mostly urban and industrial. Moreover, after the war, the region became an important industrial center in the Soviet economy and played a significant role in the Soviet military industrial complex. “After 1945,” wrote King, “Transnistria became a central component of the Soviet defense sector and its heavy industry. Some four-fifths of the region’s population was employed in industry, construction, and the service sector.”

The industrialization of Transnistria in the Soviet era also fueled the migration of East Slavs into the region, thus making it more distinct from the rest of Moldova and more “Soviet.” “Internal immigrants arrived to work in the new factories, increasing the Russian and Ukrainian portions of the population,” wrote King. “The key issue… was not how Russian the region became after the war, but how quintessentially Soviet… The primary loyalty of individuals in the region was not to Russia – even though most spoke Russian and had ties to the Russian republic – but to the Soviet Union.”

Attempts at centralization by the nationalist government in Chișinău only exacerbated the differences with Transnistria. “Soviet” elites in the latter began reacting to the nationalist elites in Chișinău. “Already in the late 1980s,” wrote King, “there developed a dynamic that would culminate in full-scale war by 1992: Every move in Chișinău that pulled the republic further away from Moscow was met by a countermove in Transnistria that drew the region itself farther away from Chișinău.” This eventually led to Transnistria militarily breaking away from Chișinău to form its own self-proclaimed republic in 1992.

Moldovan elites were likewise concerned about the Gagauz, a unique group of Turkic-speaking Orthodox Christian people whose homeland straddles the southern boundaries between Moldova and Ukraine. After the Soviet collapse, the Gagauz “made common cause with the Transnistrians” but did not go so far as to proclaim their own independent republic. Still, in December 1994, Chișinău granted them their own autonomous unit in the south known as Gagauzia. The situation has been stable and the Gagauz have likewise been granted the right to secede if Moldova decides to reunite with Romania. Chișinău offered a similar deal to Transnistria, but there has been no resolution on this to date.

In the 2000s, the head of the Moldovan Communist Party, Vladimir Voronin was elected President of the country, the first such case in the former USSR. Though claiming to be supportive of European integration, Voronin, a highly Russified Moldovan, also sought to expand ties with Russia. However, his administration did little to improve the lives of everyday Moldovans, and poverty and corruption remained major problems. A victory for the Communist Party in Moldova’s April 2009 parliamentary election, though hailed as free and fair by European observers, sparked major protests and civil unrest. Student demonstrators clashed with police, stormed the parliament, and carried the flags of Romania and the European Union, chanting slogans like “We are Romanians!” and “Down with Communism!” At least five students died because of the riots. President Voronin responded by placing the blame for the unrest on Bucharest, which denied any involvement. Three months later, Moldovan state prosecutor Valeriu Gurbulea confirmed that Romania had nothing to do with the protests.

Protests in Chișinău, April 2009 (Reuters/Gleb Garanich)

Though successful in the April 2009 elections, the newly elected parliament was unable to elect a President in June. Consequently, Voronin had to dissolve parliament, thus paving the way for snap parliamentary elections in July 2009. This election brought to power a new governing coalition of liberal political parties collectively known as the Alliance for European Integration (AEI). Voronin resigned from the presidency in September but the AEI was unable to elect a president until March 2012, when the independent judge Nicolae Timofti was finally voted into office.

As their name implies, the top priority of the AEI and its successor the Pro-European Coalition (PEC) has been EU integration and EU membership. It took advantage of Moldova’s position with the Polish-Swedish EaP initiative and quickly emerged as the most progressive ex-Soviet state in terms of EU reforms. Among other things, the AEI advanced the issue of visa liberalization in Moldova. On April 3, 2014, it was announced that there will now be a visa-free regime between Moldova and the EU’s Schengen Area. Moldova also confirmed the final version of its Association Agreement with the EU at the November 2013 Vilnius Summit to be signed in June 2014.

Further, under the AEI and PEC, Chișinău also moved increasingly closer toward Romania. In December 2009, the AEI announced that it would be removing the barbed wire fence separating their country from Romania. On December 5, 2013, the PEC recognized Romanian as the official language of the Moldovan republic. This move was welcomed by Romania’s Traian Băsescu who has long favored reunification with Moldova. On the eve on the Vilnius Summit, he stated:

Romanian President Traian Băsescu (AFP/Getty/Lionel Bonaventure)

When a nation has the opportunity to be together, it should not give up. It may not happen straightaway, but it will happen one day, because blood is thicker than water. I think this is the right time to say that we have this objective, if Moldovan people want this. I am convinced that if Moldova wants to unite, then Romania will accept.

He also stated that after joining the EU and NATO, Romania’s third priority must be reunification with Moldova, though given official Chișinău’s concerns with ethnic minorities such as the Gagauz, it would likely be less enthusiastic about taking such a step.

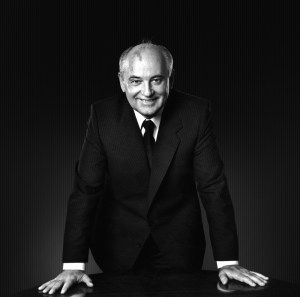

Băsescu further cautioned that “the big risk for Moldova would be a treatment with arrogance by EU – be aware, I use the word with responsibility – which would not take into account the electoral realities in Moldova.” Moldova still faces many challenges to its EU road, both domestic and foreign. Internally, Vladimir Voronin and the Communist Party advocate a strongly pro-Russian stance, ultimately favoring membership in the Eurasian Customs Union. The Communists adhere to a strong Moldovenist position, advocating a unique “Moldovan” identity and firmly rejecting the idea that the “Moldovan language” is in fact the Romanian language. “Moldova can become a European country only by joining the Customs Union,” the 72-year-old Voronin told a crowd of largely elderly anti-EU activists from the Communist Party.

Vladimir Voronin (Unimedia)

However, Voronin and the Communists are not a spent force. As Băsescu alludes, they have a substantial following within Moldova. Though they lost the July 2009 parliamentary election to the AEI coalition, the Communists still garnered 44.69% of the vote. They poll especially well in the north of the country and also among the substantial East Slavic minority of Moldova proper, which numbers about 14% of the total population. They also do well among the Gagauz in the south who fear that closer relations with Romania could threaten their hard-won autonomous status. Consequently, the possibility of Moldova’s pro-EU coalition losing to the communists is very real for Moldova in terms of its future geopolitical orientation. Still, for the immediate future, this risk is mitigated by the fact that Moldova’s next parliamentary election will not be held until November 2014, several months after Chișinău is set to sign the final version of its Association Agreement with the EU in June 2014.

There are also external challenges. Like Ukraine and Armenia, Moldova too is heavily dependent on Russian energy. It currently imports all of its natural gas from Russia, though the newly-inaugurated Iași-Ungheni pipeline with Romania promises to undermine this total dependence. A wine-producing country, Moldova also exports 28% of its wine production to Russia (for comparison, 47% of Chișinău’s exports go to the EU). A recent embargo by Moscow of Moldovan wine, due to an alleged trace of plastic contamination found in barrels of devin, has been a serious issue for the country. Some claim that the ban was politically motivated as a means of pressuring Chișinău to change its pro-EU geopolitical orientation, an assertion that Moscow has flatly denied. In addition, as many as half a million Moldovans are estimated to work illegally in Russia. Significantly, approximately the same number have Romanian passports and have departed the country to work in Western Europe, with Traian Băsescu provocatively claiming the number to be much higher, up to 1.5 million.

A Gagauz Woman Casts Her Ballot in the February 2014 Referendum in Gagauzia (Valtenia Ursu/RFE/RL)

However, Moscow’s biggest cards to play with regard to Chisinău’s EU ambitions are its distinct ethnic regions of Gagauzia and Transnistria. Gagauzia is not a breakaway region but rather an autonomous unit comprised almost entirely of ethnic Gagauz. Though content with remaining part of Moldova, the Gagauz are concerned about how joining the EU could affect their future, especially given Romania’s involvement. Recently, the Gagauz leadership held a referendum in February 2014 that rejected the country’s pro-EU aspirations and reaffirmed its right to secede from Moldova in the case of reunification with Romania. Though condemned by the Moldovan court as “unconstitutional,” this referendum was clearly intended as a warning to Chișinău against the possibility of a future reunification with Romania in which the Gagauz autonomy might be threatened. For the record, ex-communist Romania has consistently refused to grant autonomous status for any ethnic minority in its country including, most notably, the ethnic Hungarians of the Székely Land. Traian Băsescu himself has ruled out any possibility of a future Hungarian autonomy. Following the referendum, the pro-EU Moldovan government sought to reassure the Gagauz that a reunification with Bucharest was not imminent, and that the EU will actively work to better guarantee their minority rights. Whether or not the Gagauz will be adequately convinced of Moldova’s European choice remains to be seen. If left unresolved, this issue could devolve into a very serious crisis.

Aleksandr Lebed in Tiraspol, the capital of Transnistria, during the 1992 war.

Most significantly of all, there is the unresolved conflict over Transnistria. The majority of Transnistria’s population is East Slavic (Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians who collectively make up 60% in total according to the 2004 census) and Russian is the dominant language. Politically, the pro-Russian orientation is strong here and is reinforced by the presence of the Russian 14th Army (now known as the Operational Group of Russian Forces in Moldova). Aleksandr Lebed, the Bonapartist Russian strongman from the 1990s, played a key role in Transnistria’s 1992 war of independence from Moldova proper. He viewed himself as the liberator of Transnistria from the “fascists” and “ideological heirs of Antonesu” in Chisinău. He is regarded as a hero here.

Towards a potential solution

While Moldova is officially committed to returning Transnistria under its rule, it is unclear what benefit this would bring to the country as a whole. For one thing, Transnistria does not have a deep historical relationship with Moldova. Even the poet Eminescu in his famous work Doina spoke of the Romanian nation as only stretching “from the Dniester to the Tisza.” Unlike Georgia’s conflicts with Abkhazia and South Ossetia, in which the Georgians attach deep emotional and historical significance to their breakaway regions, the same really cannot be said for Transnistria and Moldova. Transnistria was attached to Moldova proper in 1940 and thus was only associated with it for 52 years until its secession in 1992. Compare that to the Georgian-Abkhazian or Georgian-Ossetian relationships which extend back several centuries into history.

Indeed, most Moldovans, according to various opinion polls, are indifferent toward Transnistria. For the vast majority, the issue ranks as the ninth or tenth priority for the population of Moldova proper. Fewer than two percent consider the issue to be the most pressing, while “five percent consider it second, well behind issues such as poverty, crime, or inflation.” According to one observer, “this stands in striking contrast to the much higher preoccupation with frozen conflicts in other post-Soviet countries such as Azerbaijan and Georgia.”

In addition to this, Transnistria can be viewed as more of a major economic liability for Chișinău than a benefit. Though Moldova currently owes virtually no debt for its gas imports from Russia, Transnistria owes approximately $4 billion to Gazprom. Moscow presently holds Chișinău accountable for this debt. The only way to get rid of it would be for Moldova to entirely relinquish its claims to the disputed territory.

Transnistrian President Yevgeny Shevchuk. An ethnic Ukrainian and anti-corruption activist, Shevchuk is keen on forging closer ties with Moscow.

Meanwhile, Transnistria’s current President Yevgeny Shevchuk, while not the Kremlin’s choice in the Transnistrian election, has continued to maintain strong ties with Moscow. An ethnic Ukrainian, Shevchuk studied in both Ukraine and Russia and was elected as a reformer committed to challenging corruption and oligarchy, not as an advocate for reunification with Moldova. After his election in 2012, he immediately met with Sergei Ivanov, one of Putin’s closest associates and an influential member of his inner-circle. He also advocated that Transnistria adopt the Russian ruble and Russian laws, with the ultimate aim of Transnistria joining the Eurasian Union.

Observing this scenario, it seems that while Moldova proper is increasingly moving closer toward the EU, Transnistria is moving very much in the opposite direction toward the Eurasian Union. A potential, logical, and peaceful solution to this problem would be the formal separation of these two entities from each other. Moldova’s pro-EU leadership could recognize Transnistria and relinquish all claims to it, while working with the authorities in Tiraspol to delineate the border between the two states. Given Transnistria’s limited viability as an independent entity, Moscow could work with Tiraspol and Ukraine to consider the possibility of reuniting the former with the latter. A solution like this would satisfy Transnistria’s pro-“Soviet” and pro-Slavic sentiments and would absolve Moldova of any lingering debt to Gazprom. It would also help reduce any sort of ill feelings in Ukraine toward Moscow for its recent incorporation of Crimea. However, such a resolution is entirely contingent on the people and the elites of Moldova and Transnistria and on how the situation in Ukraine develops. It could only work if a new government more amiable toward Moscow and Tiraspol emerges in Kiev.

It also should be noted that Moldova proper is of marginal significance to Moscow. The country is poor, landlocked, and Romanian-speaking, with few natural resources and very little geostrategic value. It is already very much integrated with the EU and a sizeable number of its citizens already have Romanian/EU passports. Additionally, the inauguration of the Iași-Ungheni pipeline will likely substantially reduce Moldovan energy dependence on Moscow. Thus, the best and most logical solution to the ongoing Transnistria problem would be its split from the Moldovan state and its eventual reunification with Ukraine.