Will Rogers (Biography)

, the noted American entertainer and radio personality, once famously joked that “Russia is a country that no matter what you say about it, it’s true.” This holds true today, especially in the Western press.

One example of this is the Russian initiative to form the Eurasian Union, a supranational union comprised of former Soviet republics. This has been largely criticized in the West as either a “New Russian Empire” or a “New Soviet Union.” In 2012, former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton referred to the project as a “move to re-Sovietise the region.” While acknowledging that the Eurasian Union will not be called “the Soviet Union,” she also stressed “let’s make no mistake about it. We know what the goal is and we are trying to figure out effective ways to slow down or prevent it.” Timothy Synder, the author of Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, went even further in his denunciation of the concept, referring to it as the realization of the anti-liberal neo-fascist Eurasianist schemes of Aleksandr Dugin. He specifically cited Dugin as “the ideological source of the Eurasian Union” and that his work constitutes “the creed of a number of people in the Putin administration.”

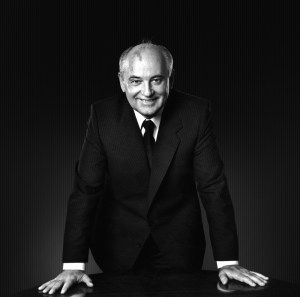

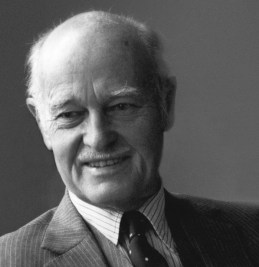

Beyond the headlines, though, what exactly is the Eurasian Union? Is it truly an anti-Western conspiracy of neo-fascists, Bolsheviks, and boogie men opposing liberal ideals worldwide which, like Soviet communism, needs to be “contained?” Or rather is it a supranational liberal economic union promoting free trade and open borders with the former Soviet republics who already share close historical, economic, and cultural links with Russia? For the answer to this question, one must turn to the history of the Eurasian Union idea. Indeed, if one explores the history of the Eurasian Union concept, one discovers that its originator was not Aleksandr Dugin, but in fact, Mikhail Gorbachev.

Mikhail Gorbachev

As the Soviet system and Soviet communism was collapsing in the early 1990s, then-Soviet President Gorbachev took a bold step that is often overlooked: he proposed the basic framework for a reformed Soviet state. The new state would be a non-communist democratic federation (under Gorbachev, the Communist Party already began to lose its monopoly on power in 1989, a fact that became official with his creation of the Soviet Presidency in March 1990).

Gorbachev anticipated a referendum in which Soviet voters would be given the choice to vote on the establishment of this new state in March 1991. This referendum on a New Union Treaty was approved by the vast majority of Soviet citizens, including those in then-Soviet Ukraine, who favored it by 82%. It should be noted that a significant number of West Ukrainian activists had boycotted Gorbachev’s referendum, but even if one were to include the boycotted votes as “no” votes, then the overwhelming majority of Ukrainians still favored Gorbachev’s new union by a wide margin. Additionally, the only other Soviet republics that boycotted the referendum were the three Baltic states (which sought independence), Moldova (which sought to reunify with Romania), Armenia (which was frustrated with Moscow over its indecision on Nagorny Karabakh), and Georgia (under the influence of nationalist dissident leader Zviad Gamsakhurdia). Other than this, the referendum passed overwhelmingly.

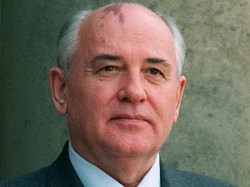

Boris Yeltsin

Despite the fact that the referendum was favored by the vast majority of Soviet citizens, it was never implemented. In August 1991, communist hardliners, who bristled at Gorbachev’s glasnost, put the Soviet leader under house arrest in Crimea. In the end, the putschists were faced down by the leader of the then-Soviet Russian republic, Boris Yeltsin and the coup collapsed. Following the coup, Gorbachev sought to pursue the establishment of the new union that the majority of Soviet citizens favored in the March referendum. However, Yeltsin insisted on a confederation of states as opposed to a state federation. Gorbachev was initially opposed, fearing that a confederation would lead to disaster. However, in the end, Gorbachev relented and backed the confederation proposal.

However, even the idea of a confederation was not realized. Without Gorbachev, Yeltsin, along with Ukraine’s Lenoid Kravchuk and Belarus’ Stanislav Shushkevich, formally dissolved the Soviet state at meeting in the Belavezha Forest. Gorbachev lost his position and the 15 Soviet republics were now formally independent states, with some, like the Baltics, Armenia, and Georgia, proposing independence referendums earlier. However, Yeltsin apparently did not want to totally severe Russia’s ties with the other former Soviet states (now known as the “near abroad”). Indeed, the Belavezha Accords also gave birth to the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), a loose association of 12 of the 15 former Soviet republics (understandably, the Baltics for historical reasons did not participate).

Nursultan Nazarbayev

During his administration, Yeltsin never formally lost sight of maintaining Russia’s links with the former Soviet states, despite major problems in Russia itself (most of which were arguably the result of his own policies). In 1992, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) was formed, initiating a sort of military alliance among the various ex-Soviet states. Two years later in 1994, in an address to a Moscow university, Kazakhstan’s Nursultan Nazarbayev proposed an early concept for an EU-style supranational union of the ex-Soviet states. Then in 1996, this idea evolved into the Treaty on Increased Integration in the Economic and Humanitarian Fields signed by Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia. This was followed by the Treaty on the Customs Union and the Single Economic Space in 1999 signed by the same countries along with Tajikistan. Finally, in 2000, the Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEC) was formed.

Again, I have cited three individuals in this historical overview: Gorbachev, Yeltsin, and Nazarbayev. All three favored some sort of integration and association among the former Soviet states prior to the major writings of Aleksandr Dugin in 1997, including his controversial fascist-Eurasianist work The Foundations of Geopolitics. The assertions that the Eurasian Union, at its heart, is a Duginist scheme do not take into account the integration processes that were already in progress within the former Soviet Union and therefore are both incorrect and anachronistic.

It can likewise be definitively concluded that, given the fact that organizations like the EurAsEC serve as a direct predecessor to today’s Eurasian Customs Union, the ideology and political philosophy of Moscow’s present-day post-Soviet integration effort is not intended to be a conspiratorial neo-fascist or anti-Western coalition. Rather, it is at its core a liberal idea, intended to promote open borders, free trade, and economic and cultural exchange among the ex-Soviet states, who already share much culture with Russia. In the words of fellow Russia watcher and commentator Mark Adomanis:

Without lapsing into cartoonish Kremlinology, I do think it’s noteworthy and important that Putin is so publicly and forcefully going on the record advancing a broad program of technocratic neoliberalism: harmonizing regulations, lowering barriers to trade, reducing tariffs, eliminating unnecessary border controls, driving efficiency, and generally fostering the free movement of people and goods. Even if not fully sincere, an embrace of these policies is healthy.

…Anything that makes Russia more open to people and commerce is positive and can only serve, in the long-term, to weaken the foundations of its current hyper-centralized system.

Efforts toward Eurasian integration continued apace under the Putin presidency. According to Mikhail Gorbachev in a 2009 interview with the Moscow-backed network RT, Ukraine seemed to have expressed interest in the project as well:

We were close to creating a common economic zone, when Kuchma was still in power. These four countries – Russia, Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan had 80% of the potential of the whole Soviet Union. It was a great force. And if you look at all the natural resources… But then many things got in the way of this process – Caucasus, Ukraine.

US President George W. Bush with Georgia’s Mikheil Saakashvili

The “things” to which Gorbachev referred were efforts by the United States to expand its geopolitical sphere of influence deep into post-Soviet territory, particularly in Ukraine and Georgia. The US administration of George W. Bush, with the aid of Western NGOs and both major American political parties, sought to promote pro-Western “color revolutions” in the ex-Soviet states. They aggressively focused particularly on Georgia, which was Moscow’s historic “center” in the Caucasus, and Ukraine, a country with which Russia shares deep historical, cultural, economic, and even personal ties. The spread of such revolutions also happily, and not coincidentally, intersected with American and Western energy interests in the region. American oil companies showed particular interest in resource-rich states like Azerbaijan and the “stans” of Central Asia.

George F. Kennan

The new leaderships of both Ukraine and Georgia also set an overtly pro-Western course to join both the EU and NATO, much to the Kremlin’s annoyance. In the early 1990s, the administration of US President George H. W. Bush squarely promised Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev that NATO would “not move one inch eastward” beyond East Germany as a means to ensure Soviet support for German reunification. However in 1997, under the Clinton administration, the United States backpedaled on its promise to Moscow by inviting several former Warsaw Pact countries into NATO and also intimating the promise of EU membership. Though accepted by Yeltsin, the expansion of NATO by Washington annoyed and antagonized Moscow. In this regard, the words of the great diplomat, George F. Kennan in February 1997 were especially prophetic:

Expanding NATO would be the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-cold war era. Such a decision may be expected to inflame the nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic tendencies in Russian opinion; to have an adverse effect on the development of Russian democracy; to restore the atmosphere of the cold war to East-West relations, and to impel Russian foreign policy in directions decidedly not to our liking.

Gorbachev echoed this sentiment in his 1999 book On My Country and the World:

The danger of a new division of the continent has arisen with NATO’s expansion to the East, which will inevitably encourage military preparations in a number of countries on the continent.

Václav Havel

However, neither Kennan’s nor Gorbachev’s words were ever heeded by Washington policymakers. Eventually, both NATO and the EU expanded to include virtually all of the former Warsaw Pact states in Central-Eastern Europe as well as the three former Soviet Baltic states. The late Czech President Václav Havel likewise observed that while the Kremlin was annoyed by NATO expansion in Central-Eastern Europe, the expansion into the three Baltic states caused even greater concern to them. Now NATO was on the very doorstep of St. Petersburg. Havel specifically recalled in his 2007 memoir To the Castle and Back:

It was no longer just a small compromise, but a clear indication that the spheres of interest once defined by the Iron Curtain had come to an end. Yeltsin had generously supported Czech membership in NATO, but the Baltic republics must have been very hard for Putin to swallow.

Feeling threatened by the prospect of further NATO expansion and by the provocative behavior of the new “color revolution” governments in Kiev, and especially Tbilisi (with Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili being especially antagonistic), Moscow redoubled its post-Soviet integration efforts. The groundwork for the present-day Eurasian Customs Union was first laid in August 2006 at an informal EurAsEC summit meeting in Sochi between Putin, Nazarbayev, and Belarus’ Aleksandr Lukashenko.

Efforts toward forming the actual Customs Union intensified in 2008, the year of the NATO Bucharest Summit, the South Ossetian war, and the start of the Eurozone crisis. They intensified even more the following year, especially after the official formation of the EU’s Eastern Partnership (EaP) program to bring ex-Soviet republics like Ukraine and Georgia into the EU. In November 2009, the Presidents of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia officially agreed to form the customs union in Minsk. On 1 January 2010, the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia (today the Eurasian Economic Community Customs Union) was officially launched. In November 2011, the leaders of the three countries met and set 2015 as the target date for establishing the new supranational union. It also recognized the Eurasian Economic Commission, paving the way for the Eurasian economic space in 2012.

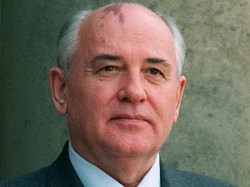

Mikhail Gorbachev (NBC)

The primary Russian motive behind the establishment of the Eurasian Union is not historic imperial ambition. In fact, from a Russian perspective, some of the ex-Soviet countries can be viewed as a liability. However, for economic, historic, geopolitical, and security reasons, they are viewed as essential. For Moscow, their necessity has been even more pronounced in light of recent American and Western efforts to aggressively expand NATO into the post-Soviet space, despite earlier promises to the contrary. Yet none of this changes the fact that the prevailing popular perception of the Eurasian Union in the West and among some in the former Soviet countries is that it is a “new Russian empire,” a sad commentary on that which is a falsely propagated historical perspective. In his

2009 interview with RT, Gorbachev, referring to the US-backed “color revolution” governments, stated that “they keep thinking that Russia wants to create a new empire.” When asked whether or not this was the case, he immediately responded:

Not at all. Putin was giving an interview to Le Figaro. He got the same question about imperial ambitions. His answer was a definite no. Russia’s position [by Yeltsin] defined the fall of the Soviet Union. If it were not for Russia, the Soviet Union would still exist. This was the first time I heard this revelation from Putin. I think we need economic co-operation [in the former USSR].

Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev expressed the same opinion in an interview with Georgian television in August 2013 where he stated that the CU “is not about restoring the Soviet Union. Who needs the restoration of the Soviet Union? We live in the 21st century.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin

The perception of the CU as a “new Russian empire” happily coincides with Western geopolitical distrust of Russia and with prevailing narratives in the Western media that Russia is engaging in “19th century diplomacy” and that Putin has “neo-Soviet” ambitions (which is a misnomer because Putin is a moderate nationalist, not a communist). Further, in April 2005, Putin himself publicly lamented the breakup of the USSR as the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the 20th century. In that quote, Putin was referring to the conglomerate of republics (USSR), not communism. Though this sentiment is widespread in the former USSR and has been even endorsed by Mikhail Gorbachev, many in the West have taken this quote as evidence of Putin’s clandestine neo-imperial agenda. The same quote has only heightened suspicions toward the CU among many in the former Soviet republics as to the real intentions of the Kremlin-backed geopolitical project. Also, a month later, Putin even clarified his remarks in an interview with German television by stating:

Germany reunites, and the Soviet Union breaks up, and this surprises you. That’s strange.

I think you’ve thrown the baby out with the bathwater – that’s the problem. Liberation from dictatorship should not necessarily be accompanied by the collapse of the state.

As for the tragedy that I talked about, it is obvious. Imagine that one morning people woke up and discovered that from now on they did not live in a common nation, but outside the borders of the Russian Federation, although they always identified themselves as a part of the Russian people. And there are not five, ten or even a thousand of these people, and not just a million. There are 25 million of them. Just think about this figure! This is the obvious tragedy, which was accompanied with the severance of family and economic ties, with the loss of all the money people had saved in the bank accounts their entire lives, along with other difficult consequences. Is this not a tragedy for individual people? Of course it’s a tragedy!

People in Russia say that those who do not regret the collapse of the Soviet Union have no heart, and those that do regret it have no brain. We do not regret this, we simply state the fact and know that we need to look ahead, not backwards. We will not allow the past to drag us down and stop us from moving ahead. We understand where we should move. But we must act based on a clear understanding of what happened.

Overall, the Eurasian Union concept is not new. It is not a Russian imperial conspiracy rooted in Duginist neo-fascist tracts, but rather a liberal pro-market project aimed at opening borders and encouraging economic development among the former Soviet states. It is this reality that the West should fundamentally understand when analyzing Russia’s Eurasian Union initiative.