The Reconsidering Russia blog and podcast have been on “hiatus” for a period of about five years. The last major activity was my interview with the late great historian Stephen F. Cohen, my friend and mentor best known for his biography of Nikolai Bukharin. Since then, a lot has happened. I completed my PhD at Ohio State, moved on to a lectureship in Yerevan, and then a postdoctoral fellowship in St. Petersburg. Over that time, the world witnessed major upheavals, including the still-ongoing war in Ukraine. All the while, I was steadily and meticulously preparing my monograph on Anastas Mikoyan and his reforms in the sphere of Soviet nationality policy during the period of Nikita Khrushchev’s Thaw.

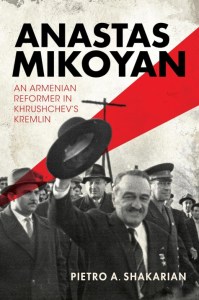

Now, I am happy to report that my Mikoyan research journey is finally nearing completion. My forthcoming book Anastas Mikoyan: An Armenian Reformer in Khrushchev’s Kremlin will be published by Indiana University Press in August 2025, and it is already listed on Amazon.com. The study is largely based on never-before-seen materials from the Russian and Armenian archives, as well as memoirs in the Russian and Armenian languages. Here is Indiana’s official description of the book:

Veteran Soviet statesman and longtime Politburo member Anastas Ivanovich Mikoyan is perhaps best remembered in both the West and the post-Soviet space as a master political survivor who weathered every Soviet leader from Lenin to Brezhnev. Less well known is the pivotal role that Mikoyan played in dismantling and rejecting the Stalinist legacy and guiding Khrushchev’s nationality policy toward greater decentralization and cultural expression for nationalities.

Based on new discoveries from the Russian and Armenian archives, Anastas Mikoyan is the first major biographical study in English of a key figure in Soviet politics. The book focuses on the Armenian statesman’s role as a reformer during the Thaw of 1953–1964, when Stalin’s death and Khrushchev’s ascension opened the door to greater pluralism and democratization in the Soviet Union. Mikoyan had been a loyal Stalinist, but his background as a native Armenian guided his Thaw-era reform initiatives on nationality policy and de-Stalinization. The statesman advocated a dynamic approach to governance, rejecting national nihilism and embracing a multitude of ethnicities under the aegis of “socialist democracy,” using Armenia as his exemplar. While the Soviet government adopted most of Mikoyan’s recommendations, Khrushchev’s ouster in 1964 ended the prospects for political change and led to Mikoyan’s own resignation the following year. Nevertheless, Mikoyan remained a prominent public figure until his death in 1978.

Following a storied statesman through his personal and professional connections within and beyond the Soviet state, Anastas Mikoyan offers important insights into nation-building, the politics of difference, and the lingering possibilities of political reform in the USSR.

Here are some preliminary reviews:

“Shakarian’s study reflects a significant amount of scientific work. Especially noteworthy is his ability to analyze historical events and personae in a context that was constantly changing throughout the lifetime of Anastas Mikoyan. His work with sources is particularly impressive.”

~Mark Grigorian, author of Yerevan: Biography of a City

“This splendid piece of research and writing deals with important issues that have not been adequately explored before in historical scholarship. The archival revelations are stunning, and Shakarian brings new light to obscured topics, showing the inner workings of the Soviet system under Stalin and Khrushchev. Well-organized, readable, and never verbose, it is a much-needed and original contribution to the field of Soviet studies.”

~Ronald Grigor Suny, author of Stalin: Passage to Revolution

“Pietro Shakarian’s remarkable, comprehensive examination of one of the great, emblematic figures of the Soviet past stands as an invaluable contribution to the study of the role of the individual in history.”

~Edward Nalbandian, former foreign minister of Armenia

“This book is unquestionably an important contribution to scholarship on Soviet policymaking and nationality policy. Mikoyan has until now been an unjustly neglected figure in Soviet policymaking. By focusing on his personal networks and groundbreaking initiatives in the field of de-Stalinization, Shakarian has made an important and invaluable contribution to greater understanding not only of the Khrushchev period, but of Soviet history as a whole.”

~Alex Marshall, author of The Caucasus Under Soviet Rule

“Shakarian’s painstaking research produces new and comprehensive insights into Mikoyan’s deft and consequential role in the reforms that came to define Nikita Khrushchev’s post-Stalin Thaw.”

~Edward P. Djerejian, former US Ambassador

“Anastas Mikoyan stands as a central yet understudied figure in Soviet politics. A faithful member of Stalin’s Politburo, Mikoyan ultimately rejected Stalinism in favor of political liberalization under Khrushchev. In this outstanding biographical study, Pietro Shakarian employs pathbreaking archival research to uncover Mikoyan’s leading role in Khrushchev’s reforms. He demonstrates that Mikoyan drew on his Armenian heritage to reorient Soviet nationality policy during de-Stalinization. This book will be essential reading for scholars of Soviet nationality policy, Khrushchev’s Thaw, and the history of the USSR more generally.”

~David L. Hoffmann, author of The Stalinist Era

Finally, here is a rare documentary (in Armenian) of Mikoyan’s visit to Armenia in March 1962, courtesy of the National Archives of Armenia in Yerevan: